The patio of the Casa Invisible in Malaga. (Photo from Elconfidencial.com)

Your blogger visits Malaga for the INURA meeting, hosted in part by the Casa Invisible social center. We learn about the city of "sun and sand", and its self-identification as a touurist paradise. Baby Picasso appears as a prominent ghost, promoting the city's many banal museums.

Arriving by train in Malaga for a meeting of urbanists, I taxied straight to the Casa Invisible. I had visited the venerable occupied social center in that touristic city briefly almost 10 years ago. La Casa was closed then, but a friend of a friend of a judge let us in. (The judge, to remain impartial, remained outside.)

La Casa Invisible then was clean, well-tended, with a lovely Andalus-style interior courtyard. I recall a tiny bookstore set into the front of it. A text about the Casa was included in our 2015 book Occupation Culture (Other Forms & JoAAP).

The social center is set amongst the narrow streets of the city’s historic district, so the taxi could only take me near the back door. A press conference for the INURA meeting I had come for was in progress.

A Different Kind of Convention

INURA is the International Network for Urban Research and Action, “people involved in action and research in localities and cities.... activists and researchers… who wish to share”.

This wasn’t really an academic meeting, although it had many of the earmarks. Originating among Zurich-based researchers, the group has been meeting in cities around Europe for decades. They learn about urban spaces through guided tours, then head to a days-long retreat to chat amongst themselves.

I went on some tours with the INURAistxs, and chatted with several of them. I did not go on the retreat.

It was a strain. I’d just returned from a month in the States and had a surgery scheduled. I fell heavily in the school of architecture, which took me out of sessions for a day. The next day I blew a mental fuse and sat insensibly during the meetings.

Despite the rigors and accidents of senior travel, this visit was imiportant to see the Casa Invisible in its ambience. I learned something about this important Spanish social center which improbably maintains itself in a city with a right-wing government cemented in place.

“Sun and Sand”

Malaga is on the southern Mediterranean “Costa del Sol”. The city and the region has been all about tourism for a long while. A main theme of the meeting then was the figuration of the city and its region through that industry. As we found, that conception is getting pretty ragged.

The Costa del Sol is the poster child of excessive overdevelopment. Long one of the more picturesque and oft-depicted parts of Spain, the region was developed as a fountain of foreign currency for the Franco dictatorship. The picturesque white villages of the Andalusian coast were drowned in a tsunami of development – mainly apartment buildings – which has never stopped. Today 30% of Spain’s economy derives from tourism.

(While Costa del Sol is rife with foreigners, I’ll note that in most parts of Spain the tourism is internal, by nationals who want to know their own highly diverse peninsula.)

Tourism for this region was meticulously constructed on top of local traditions and features of Andalusian culture. An RTVE production of the epoch, "Malaga and the Costa del Sol in 1976", on YouTube praises the "organized paradise" – jet airplanes, lavish buffets, bulls, flamenco, titty shows and lots of blonde white people. Over 40 years on, that local flavor seems to have almost entirely evaporated.

Once a Village, Torremolinos is Towers

The two INURA tours I went on focussed on the model touristic city – Torremolinos, just outside Malaga -- and on the museumification of Malaga itself.

The bus from the hostel in Malaga to Torremolinos let us off by a fast wide street sunk into a canyon of high-rise apartment buildings. We walked along this stinky road until we reached the “historic center” of the former town.

Not so long ago, this was a poor part of Spain. In ancient times, the Romans never recreated here; there are no villa sites to excavate. For them, this coastline was industrial, the site of a number of factories of the fermented fish sauce called garum.

In 75 years this town of truck gardens and subsistence fishing went from 4K to 70.4K inhabitants, 40% born outside of the province. There is in the Malaga region a kind of cosmopolitanism, albeit heavily ghettoized, and riven with new mafias and new modes of corruption.

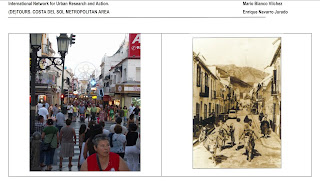

Our two guides for "Torremolinos: The origins of the touristic attraction", Enrique Navarro Jurado and Mario Blanco Vilches, circulated a paper (not online) in which they distinguished phases in tourism -- the "romantic visitors" of the 17th to 18th centuries; early 20th century elite visitors; the "boom" of mass tourism from 1960-73 after the "sun and sand" model; through 1980 a rising demand among the Spanish themselves; finally, a recalibration of the region as urban. Today the aim is "urban development of the Costa del Sol, formed by Torremolinos, Benalmádena and Fuengirola, as a continuous urban, almost a linear city".

The town cum city’s self-understanding, our guide said, is as the embodiment of “the culture of relax”. In the beginning, the canonical urbanist Henri Lefebvre visited, cupped little fishes in his hands along the beach and proclaimed Torremolinos “paradise”. The favorable micro-climate is changing planetarily now, as the summers get hotter, and the beaches need more post-season renovation.

We walked through a ‘70s-era development, the Pueblo Blanco, built like a fake Andalusian village. The white village style is more Californian-inspired than Andalucian. These chockablock apartments are studded with spolia from demolitions in the towns around Malaga.

Way Down Below She May Be

We paused at an overlook, the site of many postcards. Far below the beach and its furnishings spread out. It was dizzying. I did not descend the elevator to see. On one side below us we saw restaurant row. Those had been the fishermens’ houses along the beach where they’d pull up their boats in years past.

Our guide pointed out a modernist structure slated for demolition. In Malaga, historic buildings can be defended against the forces of development, but these efforts are mostly in vain. In part this is because, “every epoch has its imaginary”. Young people now wish to preserve other buildings linked with their childhood memories. These include some of the earliest high-rise tourist apartments.

Through all this, my emotions intervened. I hate cars, and one of the major early developments here was a highway along the beach. To me this kind of environment is a hellscape. It takes a big effort of sympathy to imagine what kind of people thrive within it. But many do, some even against the civic grain.

Baby Picasso in Malaga

I went on two city center tours, the first with our host Kike España from the Casa Invisible, and the artists Rogelio López Cuenca and Elo Vega. “The city of attractions. Urban «development» through the spell of musemification” focussed on the branding of Malaga as the birthplace of Picasso. He lived there as a child.

Screen grab from the YouTube video, "Malaga and the Costa del Sol in 1976"

Art installation of Rogelio López Cuenca, "Casi de todo Picasso" (2011) (Almost everything Picasso)

https://www.arteinformado.com/galeria/rogelio-lopez-cuenca/casi-de-todo-picasso-28563

I visited the Picasso museum in Malaga 10 years ago. It had opened in 2003 in the Juderia, the old Jewish quarter. It's a grand medieval palace which used to be the fine art museum. (That collection was moved.) What I saw there then was mostly the less exciting later work, nice but meh. Picasso’s most influential work is in other towns, like NYC and Zurich. Malaga gave his estate a free insured warehouse.

Our tour began at the artist’s birth house. That is near where the museal center city ends, and the low-rise working class Lagunillas barrio begins. (This site was part of another tour on urban displacement, “a walk through the unacceptable”.)

In 1891, at 10 years, the family left for La Coruña, and later Madrid. On a return visit to Málaga Picasso sought to borrow money from a relative. (No luck.) His formation as an artist took place in Barcelona. In 1934 he left Spain for good, refusing to return while Franco was alive. He parked his great painting Guernica in NYC. (Franco is long dead, and the artwork is back in Madrid.) Picasso was a communist, a part of his biography which is not

celebrated in Málaga. So tourists are basically walking through the Málaga of baby Pablo, as yet uninfected with problematic modern ideas.

Our artist guide, Rogelio López Cuenca, spoke of recent backward-looking architectural modifications to the plaza where the birth house sits. “To memorialize Picasso with reactionary aesthetics is a kind of revenge” on who he was – internationalist, communist, expatriate. And modernist; his engagements with post-impressionist decadence, cubism, and surrealism are not part of baby Picasso’s story. This, our guide said, was the “Malaganization of the fable of Picasso”.

“As if I Were He”

The malagueño Antonio Banderas portrayed Picasso in a TV series (Genius: Picasso 2018). He is prominent in museum openings in Malaga, acting “as a kind of medium for Picasso”.

Rogelio pointed out that the great medieval Alcazar of Malaga was destroyed by Napoleon’s troops in the early 19th century. In 1940 it was reconstructed for touristic purposes. The Roman theater, covered by an office building, was also reconstructed. The recent Museo Carmen Thyssen is the personal project of "Tita", aka María del Carmen Rosario Soledad Cervera y Fernández de la Guerra, Dowager Baroness Thyssen-Bornemisza de Kászon et Impérfalva. It houses her collection of “costumbrismo” paintings, 19th century scenes of typical Spanish life. In museum workshops, children can dress up and play archaic.

The institution claims credit for being "decisive for the dynamization and recovery of this part of the city". Pay to get a sign outside your shop and be part of the Entorno Thyssen, the "Thyssen Environment". The Casa Invisible poaches within the Baroness's cultural preserve.

Malaga has numerous other museums, including rented collections from the Pompidou and St. Petersburg. “Málaga, donde habita el arte” (Malaga, where art lives) is a city slogan. It is nearly as exciting as Frankfurt. For live creative culture, there’s Soho Málaga, “the Art District”, jump-started with street art commissions. We did not visit. I am seeing now why many grafiteros are conducting defacement campaigns against these murals, painting it over and sloganizing against them.

(In Occupation Culture (2015), I noted an early appearance of this antagonism in Copenhagen against a work by Shepard Fairey. Of course, Fairey also has a huge mural in Malaga.)

Nothing to See Here

I spent the better part of my life in the artworld, and really, most museums are boring. They’re like a sere desert landscape; nothing grows there. The more of them there are the more boring they become. What is exciting, interesting and stimulating is the artistic environment. That for the most part is not a touristic scene. La Casa Invisible is a creative environment. Not only art (wall paintings, mostly) but artists and projects in progress are to be found there.

As static displays of ostensibly lovely things, museums do one key thing in the touristic city – they underwrite consumption. In the winding streets of Malaga this urge to valorize the tiny expensive shops encrusting every street with a museal air is nearly pathetic.

The metastasizing landscape of consumption creeping into every corner of the touristic city is a process, signalled in William Carlos Williams' poem of 1920 by the line "the pure products go crazy".

Ethnographer James Clifford explains: "If authentic traditions, the pure products, are everywhere yielding to promiscuity and aimlessness, the option of nostalgia holds no charm. There is no going back, no essence to redeem."

Baby Picasso has nothing to tell us

So where is the real? Where is the active culture in Malaga? For most tourists, footsore and pained in the wallet, I’ll guess this is a moot question. For the "malagués", it matters more. If serving indifferent passing lumps of flesh fulfills you, the touristic city is the place to be. If you have some idea of developing another kind of life, maybe you’d drop in on a place like the Casa Invisible.

NEXT: A movie show and a fascist rally; a pass through the Casa Azul; and the last meeting at the Casa Invisible.

LINKS

INURA Málaga 24

https://www.inura24.org/

Moore and Smart, eds., Making Room: Cultural Production in Occupied Spaces (2015)

has a text on the Casa Invisible. Free online --

https://archive.org/details/making_room

Picture: from W. Parker Bodfish, Through Spain on donkey-back (1883). An example of the early form of elite adventure tourism in Andalusia

https://www.loc.gov/item/04005109

Soho Málaga - the “Art District”

https://malagaadventures.com/soho-art-district/

A.W. Moore, Occupation Culture : Art & Squatting in the City from Below (Minor Compositions, 2015)

PDF -- https://www.minorcompositions.info/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/occupationculture-web.pdf

introduction to James Clifford's The Predicament of Culture (1988), "The Pure Products Go Crazy"

at: https://www.writing.upenn.edu/~afilreis/88/clifford.html

Sunday, June 23, 2024

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)