Monday, December 2, 2024

La Canica Again – A Game of Marbles

In the last post, Leah Pattem told about the end of La Canica in Lavapies. This occupied bank was one of a number of long-lived social centers in Madrid. The animating idea behind La Canica was utopian. It was named for an idea of community economics, la canica, the marble, that would replace fiat money as a medium of exchange in the barrio. Now I want to explore the background of that occupation, and some of the ideation behind the dream of a community currency.

Leah Pattem wrote of what La Canica meant for the community in Lavapies. It was a center for the the movements fighting to maintain reasonable rents in the face of private equity interests which are sucking up apartments all over Spain.

But that is not why it was occupied. What does it mean for activists to take a bank? To take a school? Are these vacant buildings simply targets of opportunity?

Photo by Leah Pattem

In this post I’ll pick a bit at the ideology behind La Canica, the dream they were dreaming through their ongoing collective struggles. I’ll also try an iconographic reading of the now-expunged mural on the exterior wall of the expropriated bank branch.

Some of the most useful and strongly supported occupations in Madrid have taken place in abandoned educational institutions – that was the late Ingobernable (2017-19), and the freshly evicted La Atalaya (2014-24). While taking an abandoned bank was something new, it had been prefigured.

The Las Agencias activist art group organized ludic dances in banks during the ‘90s before the time of the crisis (Leónidas Martín, 2022). The great assemblings of 15M in 2011, provoked by politicians’ response to the financial crisis of 2008, cohered the radical movements like never before. During the years after, when the evictions of long-time rental tenants started to mount up, activist collectives took a new tack.

In the spring of 2016, activists took a bank in the Gracia barrio of Barcelona. They called it Banc Expropiat, and the struggle to hold that premises went on for years. In the fall of that year La Canica was taken in Madrid, christened Banco Expropriado.

(It was not the first here. Another group of anti-fascists and feminists took a closed office of the Caja Madrid in Moratalez, well outside the center city. I visited that one, called the Bankarrota.)

What Does This Mean?

These occupations add up, like the cascading clacks in a game of marbles, to a set of actions that propose a different kind of economic arrangement – a solidarity economy. The organizers of La Canica explained that they were building “a network of exchange… in various neighborhoods” in Madrid, promoting “the formation of cooperatives and the collectivization of resources and means of production. It is, in this sense, a tool that is being very useful for the direct and common organization of our lives, allowing goods to circulate between us by reducing our dependence on the Euro and wage labour” (Daniel Martin, 2016).

The symbol of this solidarity economy was the ostensibly valueless toy marble, proposed as a community currency. Artists love to make their own money. As an antiquarian, and one-time junior philatelist, I collected this stuff. I got “boniatos” from Madrid’s own co-op economy fair years ago. I did not trade mine in for lunch, as you can see then-mayor Manuela Carmena doing in the photo.

The mayor Manuela Carmena fingering her boniatos in 2015

My favorite piece of this kind of local currency was a scrip used at the Earthaven community in North Carolina. It passed from hand to hand, with multiple signatures of its users as validations. One fellow was persuaded to cash his out to me. I always hoped to pass by La Canica and buy up some marbles, but I never did.

Maybe there’s still a chance, as the Nodo de Producción de Carabanchel, closely involved in La Canica, was active as recently as last year. Carabanchel is a quickly gentrifying barrio of mixed residences and workshops, the coming artsy-fartsy part of the city. I’ve blogged about events at the social center there, ESLA Eko. But I’ve never seen those mythical mystical marbles.

Beats for Resistance

A manifesto still on the Nodo dePdeC website references the electronic music festival in 2023 that was shut down by the police (see my O&P post, “More Police, Less Music?”). It expresses a clear political intent behind this cultural program, a program which the city recognized as dangerous.

This is the convergence of culture and politics which artists are putting up against the bullfighters managing the regression of cultural agencies in rightwing controlled parts of Spain, the culture that rejects the compromises necessary to work in institutional spaces and, like the Pichifest zine fair, organizes in okupas.

The Mural at La Canica

La Canica was decorated with a very elaborate mural which has been whitewashed. Who did this mural, and what does it mean? I can read the many hands – reaching, being severed, bleeding out – as an allegorical representation of people’s interactions with the financial system as embodied by the bank that once occupieid the storefront. The fingers are being damaged, and seem to be looking to feel out a better way. The floating marbles, "las canicas", can signify that way which the fingers just can't seem to grasp.

Photo by Leah Pattem

Even the uphill part of the painting, the super-ornamental tattoo-like letters, is hard to read and cryptic in meaning: “Quien roba un ladron” might read as "S/he who steals" or "S/he is a thief" or even "Who robs the thief".

photo at: thediscoveriesof.com/madrid-graffiti

The artist(s) surely know their intentions best. It's signed, it seems, “ART SEN ALE”, which I couldn’t search up. In a sense, most street art reads as anonymous, circulating as images and not as authorial works. They are kind of public mysteries. Leah Pattem blogged on this several years ago: "Discover the dark messages hidden in Madrid’s street art" (11 November 2018 https://madridnofrills.com/madrid-street-art/) writing, “Although street art is deeply connected with gentrification, it often gives a voice to the victims.”

In truth, a lot of this art isn’t really that hard to figure out!

The Whole Thing Is a Cruel Joke

Exchange is mysterious. Money is ridiculous. Maybe it is like democracy, the least worst system so far for allocating the means of subsistence and production. Only now power and money have pretty much collapsed into each other. Those who have it are gaming it fiercely in the form of equity derivatives and crypto-currencies. The absurdity is patent.

But what, like the mystical canica, could possibly replace money? That is the question, which the painted mural cannot envision, although it pictures clearly the harm bank finance does.

I also collected what is called “primitive money”, mostly African. I was delighted once to get a small bunch of what sellers called “Kissi pennies”. The story about how this "money" was supplanted on a website about Liberia is instructive, and involves French and British colonial governance, and the U.S. rubber company Firestone.

The French have always loved les monnaies primitive. Since early days their colonists have had to work out how to eliminate local indigenous systems of exchange in order to enslave populations to the system of the franc. Image search = “acheter des monnaies primitives” to see the incredible variety of forms devised for who-knows-what types of transactions in Africa.

Kissi "pennies"

The go-to book in Engliish on “primitive money” is still Paul Einzig, Primitive Money: In its Ethnological, Historical and Economic Aspects (1950). Einzig was a financial journalist specializing in the analysis of international money markets.

How these objects encoded value and how they were transacted should not be a question for the theorists of supercession, like Einzig, but for economic anthropologists.

When I wrote my text on the political economy of art, I looked to the best known of these, David Graeber. I found his Toward an anthropological theory of value : the false coin of our own dreams (2001), based on his fieldwork in Madagascar, rather inscrutable. (Too shy, I did not try to contact him while he was still alive.) The book by his colleague, Keith Hart Money in an unequal world (2001), was more useful.

Like everybody else, Graeber began with Marcel Mauss, Essai sur le don. Forme et raison de l'échange dans les sociétés archaïques (1925), in translation as An Essay on the Gift. (Note, he writes “archaic”, not “primitive”.) Mauss’s thought inspired the French journal La Revue du M.A.U.S.S., which Graeber attended. (His essay Graeber’s essay "Give It Away" is on their website now.]

These ideas fired artists’ thought at the turn of the century. That’s clear in Ted Purves’ edited collection of texts, What we want is free : generosity and exchange in recent art (2nd edn., 2005), in which different artists tell how they realized the gift in their practice.

So it’s possible, on a local, episodic, experimental level, to loosen the grip of money on our collective throats. How to do that is an art. It is the art of acting, as the title of a recent book of essays on Graeber’s work has it, “As if already free”.

Farewell to La Atalaya

It is something of a dark time now for idealists. Last month another okupa was evicted, La Atalaya in Vallecas. For ten years La Atalaya had been a a multi-purpose space inside a big abandoned school. It had a library, a learning program, a metal-working studio and bicycle workshop, and multiple recreational spaces, including a boxing gym, skate ramp, and urban garden. I attended a fiesta there a few years ago. The former schoolyard was packed with children enjoying circus performances, puppet shows, and each other.

It is dispiriting when important self-organized centers are closed without notice and without negotiation. Social and recreational needs which are fulfilled in those places are simply amputated. Since it is Vallecas, a traditionally resistant barrio of Madrid, we can be sure that this blood will rise again.

LINKS

#BancoExpropriado #SolidarityEconomy

Leónidas Martín, “From Las Agencias to Enmedio: Two Decades of Art and Social Activism – Part 2 of Preparing to Exit: Art, Interventionism and the 1990s”, 15 Nov 2022

https://internationaleonline.org/contributions/from-las-agencias-to-enmedio-two-decades-of-art-and-social-activism-part-2/

La Bankarrota | centro político kolectivizado

https://labankarrota.noblogs.org

22 abr 2016 — Una antigua sucursal, no de Bankia, sino de Caja Madrid. Ha llovido mucho desde la última vez que sus propietarios se preocuparon por él, pero …

Daniel Martin, "Activistas de Banco Expropiado 'okupan' y rebautizan una antigua sucursal de Bankia en Madrid", 21 October, 2016

https://www.elmundo.es/madrid/2016/10/20/58091ad5468aebaf568b45b2.html

Community Currencies

Ester Barinaga and team at Lund University, Sweden

https://www.lusem.lu.se/organisation/research-centres/sten-k-johnson-centre-entrepreneurship/research-sten-k-johnson-centre-entrepreneurship/community-currencies

Más de 30.000 boniatos se intercambiaron en La Feria

https://www.economiasolidaria.org › Noticias June, 2015

Más de 30.000 boniatos se intercambiaron en La Feria ... En la III Feria de Economía Social y Solidaria, organizada por el Mercado Social de Madrid (MES) y la Red …

Nodo de Producción de Carabanchel – Nodo de producción

https://nodocarabanchel.net/

Sync! (°͜ʖ͡°) [smiley face] festival at ESLA Eko

“Política a 126 BPMs: Manifiesto”

https://sync.encamino.es/

Occupations & Properties, "More Police, Less Music? “I See That, and Raise You a Marble”, Sunday, April 23, 2023

https://occuprop.blogspot.com/2023/04/more-police-less-music-i-see-that-and.html

Kissi Money or ‘Money with a Soul’

https://liberiapastandpresent.org/kissi.htm

La Revue du M.A.U.S.S.

https://www.revuedumauss.com.fr/

Graeber’s essay "Give It Away"

https://www.revuedumauss.com.fr/Pages/ABOUT.html

Holly High & Joshua Reno, eds., As if already free : anthropology and activism after David Graeber, 2023

Roberto Iannucci, "La Atalaya, el pulmón social de Vallecas al que Almeida ha dado la puntilla en su guerra contra los centros autogestionados", Publico, 28 November 2024

https://www.publico.es/sociedad/atalaya-pulmon-social-vallecas-cargado-almeida-guerra-centros-autogestionados.html

Tuesday, November 5, 2024

The End of “La Canica” -- the "Anti-Bank" in Madrid

Photo of La Canica before eviction by Leah Pattem

Guest post by Leah Pattem of Madrid No Frills

Editor’s Introduction – An occupied bank on a main street of Madrid’s Lavapiés neighborhood was evicted after nearly a decade of operation. Following the 15M movement of 2011, sparked in large part by the collapse of banks in Spain, the many vacated premises of failed banks became prime targets for occupations. Everyone could see what that meant. The okupa La Canica launched with a utopian anti-capitalist mission – to replace the monetary system itself with a local community-based currency. The governing assembly quickly involved themselves in more practical issues, particularly housing, as Leah Pattem explains in this guest post.

Around fifty residents of Calle Tribulete 7 wait outside La Canica for the Sindicato de Inquilinas to arrive – they’re the one with the keys. Neighbours have come together to discuss their next strategic move in the fight against their eviction. Just a few months earlier, their homes had been purchased en masse by Elix Rental Housing, an American vulture fund which specialises in property speculation and who has requested them all to leave.

Residents aged between 93 and four years old begin entering. The more able unpack an eclectic collection of chairs, from comfortable office chairs and even an antique armchair to hard wooden benches and the iconic white plastic chairs. An uneven circle forms as close to the edges of the room as possible so that everyone can squeeze in without creating a second row. A small pop-up crèche forms by the stairs where children can play quietly as the adults talk. Stories about tall men in suits are shared, and how they entered the building without warning and knocked on residents’ doors. One neighbour has heard through the grapevine how to delay receiving an eviction notice – just don’t accept it from the postal worker. What I didn’t know at the time was that I was filming one of the last meetings in La Canica.

My first memory of the premises was as a Bankia bank. Many difficult conversations will have been had here as homeowners were told they were going to be evicted. But I also know there were moments of collective euphoria as housing activists succeeded in negotiations to stop evictions.

Following the bank’s closure, the commercial unit remained abandoned but still in the hands of the bank. After a few years, in 2016, a group of activists performed a profound act of subversion: they broke in, changed the locks, and La Canica was born. For the best part of eight years, the okupa was a community centre for Lavapiés residents and an important meeting space for the neighbourhood’s collectives.

Everyone Was Welcome (Almost)

There were rules: everyone was welcome – except for politicians, businessmen, security forces, priests and any other person who attempted to exercise authority. I fondly remember the multi-coloured wall of Post-it notes offering olive oil, therapy sessions, and language classes for children among other things. It was the structure of a counter-economy – get help putting up shelves for your neighbour in exchange for a home-cooked meal. The transaction doesn’t have to be equal in time or financial worth, only equal in personal value, and always accompanied by conversation.

The storefront today (photo by Leah Pattem)

La Canica also provided business support to Lavapiés’ migrant entrepreneurs. For a few years, up until the pandemic, Mauritanian farmer Usman sold his vegetables here one evening per week. He rents an allotment in Rivas, Madrid’s communist-run neighbourhood, where he grows a diverse range of organic fruits and vegetables. You would never know what you were going to get, including the occasional communist snail or spider. Usman would offer internships and the opportunity to learn how to farm. It was an expansion of La Canica’s counter-economy beyond Lavapiés.

But community spaces in the neighbourhood – both those registered with the town hall and those occupied – have been under increased attack in recent years. At times, it feels like the neighbourhood is swimming inside a wave sent to wipe us out. By closing social centres, removing municipal benches and cutting down trees to make squares so unbearably hot on summer nights, there are fewer opportunities for neighbours to talk and, therefore, fewer exchanges of empowering information happen, such as how to avoid being evicted.

Free Spaces Are Necessary

Free and organised spaces where it’s not required to buy a drink, and where there’s enough room to have structured meetings, are essential for local movements. Lavapiés has more collectives than any other Madrid neighbourhood – it’s infamous for organising, and the authorities know it. What many call gentrification is actually a deliberate act of social disruption and results in the dispersal of community structures. The authorities are trying to divide and conquer Lavapiés, and their closing of La Canica is part of the plan.

In the last La Canica meeting with residents of Tribulete 7, they planned a protest, a street performance, a group negotiation with the Elix company people, their press strategy, two documentaries about them – including mine – and another meeting. This is one of the most unionised buildings I’ve ever seen, and their strength and ability to organise is in huge part thanks to decades of resistance culture in Lavapiés and, of course, free spaces such as La Canica.

In June this year, I woke up to the news that La Canica had been evicted. The building is now undergoing works and, according to construction workers, it will be four self-contained tourist apartments, all of which will be unlicensed because the council is no longer granting new licences. The former okupa no longer belongs to us in any form – not even as a McDonald’s that at least lets us enter.

Lavapiés may have lost yet another okupa to unregulated tourism, but the hunt for the next empty building is already underway. There are dozens in the neighbourhood alone gathering dust and value. Once inside and locks changed, the community will simply pick up where they left off.

This post was supported by the Solo Foundation, NYC, Martin Wong Fund

NEXT -- La Canica Again -- A Game of Marbles

LINKS

Madrid No Frills

https://madridnofrills.com/

Sindicato de Inquilinas https://www.instagram.com/inquilinato_madrid/

#inquilinato_madrid

"52 flats at Tribulete 7 are facing mass eviction but tenants are fighting back"

https://madridnofrills.com/52-flats-at-tribulete-7-are-facing-mass-eviction-but-tenants-are-fighting-ba ck/

"From Mauritania to Lavapiés: meet Usman, the alternative vegetable farmer"

https://madridnofrills.com/huerto-de-usman/

"No a la Tala!’: As Madrid’s mass tree felling begins, residents are fighting back"

https://madridnofrills.com/no-a-la-tala-as-madrids-mass-tree-felling-begins-residents-are-fighting-back/

"Madrid’s climate inequality: temperature readings reveal 15-degree difference between rich and poor barrios"

https://madridnofrills.com/termometrada/

"‘Soy Tribulete 7’: Brand-new documentary in-the-making launches crowdfunding campaign"

https://madridnofrills.com/soy-tribulete-7-brand-new-documentary-in-the-making-about-lavapies-fight-back/

Wednesday, July 17, 2024

In Málaga: The Case of the Casa Invisible, Post #2

Image from video by Castro and Ólafsson

In this post I dig down on the Casa Invisible itself, the beleaguered social center in Malaga's historic center. Long an oasis for creatives and thinking people, and a center for activist organizing and strategy, "el Invi" has been under siege by the conservative government for years. Artists and institutions have pitched in to help in the resistance. Now a new space, Casa Azul and the Suburbia bookstore and publishing center, has joined in as another node of creative resistance to the banal touristification of Malaga.

In my last blog post on the trip to Málaga, I described the decades-long manic touristic development in that city and region. The heat and noise of all that was explicated in the 2024 INURA meeting I attended.

The most hyperbolic example I didn’t even mention, a gigantic luxury hotel proposed for the harbor, el gran pepino (cucumber), as prominent as the Colossus of Rhodes. The plan is the cherry on top of a fine case of capitalist rational madness. (Although unacknowledged, the money is said to come from oil sheiks.)

I didn’t come to the conference for the comic tragedy of Spanish Babbitry. I came to learn about the Casa Invisible, an inspirational Spanish social center of creative thinking people where much of the conference was held.

On the last day of the INURA meeting, our principal host, Kike España, led a tour of the building.

Kike in the nightclub of the Casa Invisible

A Palace in Commons

This 1876 Neomudéjar (Moorish style) palace has had many lives; it was a nightclub, twice a school and much more besides. It’s spectacular, but shabby. Renovation costs are estimated at a million euros. Compared to my last visit 10 years ago, La Casa today seemed disused. Signs of former creative glory abounded – a leftover theater prop, a complex mechanical face-wall; murals, and remains of art exhibitions; a compact bar and disco space which no longer operates. The free store, which was not on the tour, is still meticulously kept. A woman tidying up smiled as I peeked in.

The Casa Invisible was occupied “with a key” in 2007, since some apartments were rented within the city-owned building. The first activities there took place during a week-long festival of cinema and “free culture”. The house was named after Los Invisibles a novel by the Italian author Nanni Balestrini.

In 2011-12 the collective had an agrement with the city, but they never arrived at the most important part – the cession of the building. Now they have a “cession en precario”, a de facto tolerance of their presence.

Wall painting by Os Gemeos

Conditions are difficult at La Casa (also called “el Invi”). They have no running water, and must truck in giant cubes. The city constantly interferes with the cooperatives working in the space. “The secret police are always around,” and they have piles of denuncias (complaints) against them.

Museums Stand By

In their struggle to remain in their broken-down palace La Casa has had support from the Reina Sofia museum in Madrid (MNCARS), and the Arteleku center in San Sebastián, and the Pompidou in Paris. They host gatherings of academics like INURA, and the 2022 "Multiplicity", a congress on the "future of cultural policy in Europe" with drop-in stars like Hito Steyerl and ruangrupa.

Other support from the European institutional sector comes in the form of funded projects. Under the rubric of Arte Útil, the artist team of Libia Castro and Ólafur Ólafsson were commissioned to produce “The Rehabilitation of La Casa Invisible—Chapter I”. As explained in an e-flux broadside, the artists intend to “rethink the architectural project through art, weaving new networks of collaboration and advocating to restart the dialogue with the City Council”. They began with a video work. (See image above.)

The rehabilitation project the artist duo support was to be executed in phases so that activity in La Casa does not have to cease. Despite initial approval by a city agency, politicos with Ciudadanos put the brakes on the project. Although that political party was vaporized in the last election, the cession of La Casa still does not advance.

An Arte Útil

The conception of an Arte Útil (roughly "useful art") which brands Castro and Ólafsson’s project was developed by Cuban artist Tania Bruguera and colleagues, working at the Queens Museum, NYC, Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven, and in Havana. A stroll through their online archive of hundreds of projects that conform to the rubric is a virtual history of social practice art in the 21st century.

The ideology behind their work is clear in the e-flux broadside. It is based in ideas of the "right to the city", a concept enunciated by Henri Lefebvre in 1968, elaborated by many other urban theorists, including David Harvey, and adopted as a banner by activists.

Suburbia and the Casa Azul

The INURA meeting was also organized out of the Casa Azul, a newer site in the Lagunillas barrio of Malaga. Lagunillas is undergoing a process of radical reconstruction, with old low houses (casas bajas) being evicted, closed up, and rebuilt. Gerald Raunig, the Austrian theorist and activist, snagged a building early on, and his gang has built up a bookstore called Suburbia, a print shop and a meeting space there.

Raunig has been at the center of online theory networking for decades, most prominently European Institute for Progressive Cultural Policies (EIPCP) and its ramified platforms. They’ve been “a kind of networking of European cultural and artistic institutions with the aim of collaboratively carrying out artistic projects and organizing discursive events that accompany them”, part of the “transnational struggle against neoliberal hegemony” which “clearly refers to the specific activism of the ‘anti-globalization’ movement”. (Buden, 2007)

La Casa Azul and Suburbia together comprise a kind of a theoretical redoubt, an egghead montagnard encampment, with Raunig its own Subcomandante, a complement and a fallback in case the Casa Invisible should fall.

Depression Surfaces

The INURA meet was exhausting for me. After our last dinner in the lovely patio at La Casa, I felt a sense of sadness… and a definite tinge of hangover from the night before. The Casa Azul seems cool, and offers an encouraging way forward for alternative culture in Malaga. But a sense of doom was hanging over the Casa Invisible that evening.

Kike España was downbeat. All ways forward are blocked by the city which has cut off the water, forbids income-generating activity, and sends in undercover police in a constant campaign of destabilization. The place is being suffocated.

The focus of the Malaga activists that night was on the upcoming Spain-wide march for housing on 29 June. The assembly of the Casa Invisible, Kike said, is some 90 participants. “Years ago all of us were living in the center of Malaga. Now none of us are.” Their neighborhood became gentrified out from under them, apartments turned into tourist lodging.

The sign "Entorno Thyssen" brands the district around the Casa Invisible as a dependent territory of the mediocre museum

Throughout the INURA, the focus was on the bigger picture, madcap gentrification in Malaga, and the city’s unaffordability for its residents. As it turned out, the 29J mobilization put thousands into the streets all over the country.

Reactionary Fiestas

Our dinner the evening before, in a seaside restaurant with lavish table service, happened alongside another event at the same place celebrating the mayor who has refused the cession to La Casa. That was weird, passing all the suits and ties on the way to our tables.

“Go say hi to him,” I suggested to Kike. He gave me a wan look. The dinner moved forward in a tone of blunted sarcasm.

On the final evening we attended a screening of short films, old and new about the city. As we lined up to enter the theater, a rally for the extreme right Vox party was taking place nearby, in front of the Roman theater. It was a real Weimar scene, with lefties lining up for a film and excited reactionary politicians fulminating to a large crowd.

Theater-goers in line. Beyond them is the green awning of the Vox rightwing party, and their rally in full swing.

This is the rhythm of politics: Soon after, the extreme right took many seats in the EU parliament. The sense of depression on the left turned to fear. Then a united front pushed back the neo-fascist party in France, and cheer returned.

What Has Been, What Could Be

You can see La Casa Invisible in its early glory is shown in the five minute video "LIPDUB con Verdiales en la Casa Invisible" made in 2011. A complex “poor” production, it's joyful and very Andalusian. It’s one of the best social center videos I've ever seen. I played it in presentations many times, as it so clearly expresses the practical utopia social centers like La Casa aspire to create.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BAMVnq6vCpI

The Casa is an active culture wtihin the city – rough, at times secreting toxins, in contrast to the smooth spaces of administrated culture. It’s the kind of place where things happen, not where objects are kept to be admired. The institutional support “el Invi” has received from major museums and local academies is a clear recognition of the vital importance of live culture.

As it has ever been, it’s unclear that the weight of a collective of academics and artists, no matter their support, can counterblance the big capital which Malaga politicians serve.

Picasso is dead. The “invisible creators” crying out for a space ito thrive amidst the touristic tombscape are very much alive.

LINKS

Paula Corroto, “Otra cultura es posible en Málaga: historia de una casa (invisible) al borde del desalojo”, 18 December 2021

https://www.elconfidencial.com/cultura/2021-12-18/casa-invisible-desalojo-malaga_3341786/

Gerald Raunig, “Casa Invisible is here to stay! Against the eviction of the Invisible, against Mall-aga, against the compliant city”; July 2018

https://transversal.at/blog/Invisible-is-here-to-stay

"Multiplicity", a congress on the "future of cultural policy in Europe" at the Casa Invisible

[the multiplicity site at lainvisible.com is flagged by Google as malware. It isn't. Don't know why the monopoly thinks that. You can access it via Duck Duck Go, and likely other browsers. It has the more complete register of the conference.

https://transversal.at/blog/multiplicity-es

Libia Castro & Ólafur Ólafsson and La Casa Invisible

The Rehabilitation of La Casa Invisible—Chapter I; December 16, 2023–January 26, 2024

https://www.e-flux.com/announcements/583257/libia-castro-lafur-lafsson-and-la-casa-invisiblethe-rehabilitation-of-la-casa-invisible-chapter-i/

"About" Arte Útil

Arte Útil roughly translates into English as 'useful art' but it goes further suggesting art as a tool or device. Arte Útil draws on artistic thinking to imagine, create and implement tactics that change how we act in society.

https://www.arte-util.org/about/colophon/

Hundreds of projects, a virtual history of social practice art, are archived with links at

https://www.arte-util.org/projects/

Transversal website

https://transversal.at/

Boris Buden, “¿Qué es el eipcp? Un intento de interpretación”, 2007

https://transversal.at/transversal/0407/buden/es

Sunday, June 23, 2024

A Study Visit to Malaga, Home of the Casa Invisible, Post #1

The patio of the Casa Invisible in Malaga. (Photo from Elconfidencial.com)

Your blogger visits Malaga for the INURA meeting, hosted in part by the Casa Invisible social center. We learn about the city of "sun and sand", and its self-identification as a touurist paradise. Baby Picasso appears as a prominent ghost, promoting the city's many banal museums.

Arriving by train in Malaga for a meeting of urbanists, I taxied straight to the Casa Invisible. I had visited the venerable occupied social center in that touristic city briefly almost 10 years ago. La Casa was closed then, but a friend of a friend of a judge let us in. (The judge, to remain impartial, remained outside.)

La Casa Invisible then was clean, well-tended, with a lovely Andalus-style interior courtyard. I recall a tiny bookstore set into the front of it. A text about the Casa was included in our 2015 book Occupation Culture (Other Forms & JoAAP).

The social center is set amongst the narrow streets of the city’s historic district, so the taxi could only take me near the back door. A press conference for the INURA meeting I had come for was in progress.

A Different Kind of Convention

INURA is the International Network for Urban Research and Action, “people involved in action and research in localities and cities.... activists and researchers… who wish to share”.

This wasn’t really an academic meeting, although it had many of the earmarks. Originating among Zurich-based researchers, the group has been meeting in cities around Europe for decades. They learn about urban spaces through guided tours, then head to a days-long retreat to chat amongst themselves.

I went on some tours with the INURAistxs, and chatted with several of them. I did not go on the retreat.

It was a strain. I’d just returned from a month in the States and had a surgery scheduled. I fell heavily in the school of architecture, which took me out of sessions for a day. The next day I blew a mental fuse and sat insensibly during the meetings.

Despite the rigors and accidents of senior travel, this visit was imiportant to see the Casa Invisible in its ambience. I learned something about this important Spanish social center which improbably maintains itself in a city with a right-wing government cemented in place.

“Sun and Sand”

Malaga is on the southern Mediterranean “Costa del Sol”. The city and the region has been all about tourism for a long while. A main theme of the meeting then was the figuration of the city and its region through that industry. As we found, that conception is getting pretty ragged.

The Costa del Sol is the poster child of excessive overdevelopment. Long one of the more picturesque and oft-depicted parts of Spain, the region was developed as a fountain of foreign currency for the Franco dictatorship. The picturesque white villages of the Andalusian coast were drowned in a tsunami of development – mainly apartment buildings – which has never stopped. Today 30% of Spain’s economy derives from tourism.

(While Costa del Sol is rife with foreigners, I’ll note that in most parts of Spain the tourism is internal, by nationals who want to know their own highly diverse peninsula.)

Tourism for this region was meticulously constructed on top of local traditions and features of Andalusian culture. An RTVE production of the epoch, "Malaga and the Costa del Sol in 1976", on YouTube praises the "organized paradise" – jet airplanes, lavish buffets, bulls, flamenco, titty shows and lots of blonde white people. Over 40 years on, that local flavor seems to have almost entirely evaporated.

Once a Village, Torremolinos is Towers

The two INURA tours I went on focussed on the model touristic city – Torremolinos, just outside Malaga -- and on the museumification of Malaga itself.

The bus from the hostel in Malaga to Torremolinos let us off by a fast wide street sunk into a canyon of high-rise apartment buildings. We walked along this stinky road until we reached the “historic center” of the former town.

Not so long ago, this was a poor part of Spain. In ancient times, the Romans never recreated here; there are no villa sites to excavate. For them, this coastline was industrial, the site of a number of factories of the fermented fish sauce called garum.

In 75 years this town of truck gardens and subsistence fishing went from 4K to 70.4K inhabitants, 40% born outside of the province. There is in the Malaga region a kind of cosmopolitanism, albeit heavily ghettoized, and riven with new mafias and new modes of corruption.

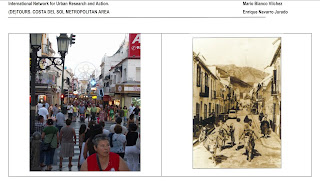

Our two guides for "Torremolinos: The origins of the touristic attraction", Enrique Navarro Jurado and Mario Blanco Vilches, circulated a paper (not online) in which they distinguished phases in tourism -- the "romantic visitors" of the 17th to 18th centuries; early 20th century elite visitors; the "boom" of mass tourism from 1960-73 after the "sun and sand" model; through 1980 a rising demand among the Spanish themselves; finally, a recalibration of the region as urban. Today the aim is "urban development of the Costa del Sol, formed by Torremolinos, Benalmádena and Fuengirola, as a continuous urban, almost a linear city".

The town cum city’s self-understanding, our guide said, is as the embodiment of “the culture of relax”. In the beginning, the canonical urbanist Henri Lefebvre visited, cupped little fishes in his hands along the beach and proclaimed Torremolinos “paradise”. The favorable micro-climate is changing planetarily now, as the summers get hotter, and the beaches need more post-season renovation.

We walked through a ‘70s-era development, the Pueblo Blanco, built like a fake Andalusian village. The white village style is more Californian-inspired than Andalucian. These chockablock apartments are studded with spolia from demolitions in the towns around Malaga.

Way Down Below She May Be

We paused at an overlook, the site of many postcards. Far below the beach and its furnishings spread out. It was dizzying. I did not descend the elevator to see. On one side below us we saw restaurant row. Those had been the fishermens’ houses along the beach where they’d pull up their boats in years past.

Our guide pointed out a modernist structure slated for demolition. In Malaga, historic buildings can be defended against the forces of development, but these efforts are mostly in vain. In part this is because, “every epoch has its imaginary”. Young people now wish to preserve other buildings linked with their childhood memories. These include some of the earliest high-rise tourist apartments.

Through all this, my emotions intervened. I hate cars, and one of the major early developments here was a highway along the beach. To me this kind of environment is a hellscape. It takes a big effort of sympathy to imagine what kind of people thrive within it. But many do, some even against the civic grain.

Baby Picasso in Malaga

I went on two city center tours, the first with our host Kike España from the Casa Invisible, and the artists Rogelio López Cuenca and Elo Vega. “The city of attractions. Urban «development» through the spell of musemification” focussed on the branding of Malaga as the birthplace of Picasso. He lived there as a child.

Screen grab from the YouTube video, "Malaga and the Costa del Sol in 1976"

Art installation of Rogelio López Cuenca, "Casi de todo Picasso" (2011) (Almost everything Picasso)

https://www.arteinformado.com/galeria/rogelio-lopez-cuenca/casi-de-todo-picasso-28563

I visited the Picasso museum in Malaga 10 years ago. It had opened in 2003 in the Juderia, the old Jewish quarter. It's a grand medieval palace which used to be the fine art museum. (That collection was moved.) What I saw there then was mostly the less exciting later work, nice but meh. Picasso’s most influential work is in other towns, like NYC and Zurich. Malaga gave his estate a free insured warehouse.

Our tour began at the artist’s birth house. That is near where the museal center city ends, and the low-rise working class Lagunillas barrio begins. (This site was part of another tour on urban displacement, “a walk through the unacceptable”.)

In 1891, at 10 years, the family left for La Coruña, and later Madrid. On a return visit to Málaga Picasso sought to borrow money from a relative. (No luck.) His formation as an artist took place in Barcelona. In 1934 he left Spain for good, refusing to return while Franco was alive. He parked his great painting Guernica in NYC. (Franco is long dead, and the artwork is back in Madrid.) Picasso was a communist, a part of his biography which is not

celebrated in Málaga. So tourists are basically walking through the Málaga of baby Pablo, as yet uninfected with problematic modern ideas.

Our artist guide, Rogelio López Cuenca, spoke of recent backward-looking architectural modifications to the plaza where the birth house sits. “To memorialize Picasso with reactionary aesthetics is a kind of revenge” on who he was – internationalist, communist, expatriate. And modernist; his engagements with post-impressionist decadence, cubism, and surrealism are not part of baby Picasso’s story. This, our guide said, was the “Malaganization of the fable of Picasso”.

“As if I Were He”

The malagueño Antonio Banderas portrayed Picasso in a TV series (Genius: Picasso 2018). He is prominent in museum openings in Malaga, acting “as a kind of medium for Picasso”.

Rogelio pointed out that the great medieval Alcazar of Malaga was destroyed by Napoleon’s troops in the early 19th century. In 1940 it was reconstructed for touristic purposes. The Roman theater, covered by an office building, was also reconstructed. The recent Museo Carmen Thyssen is the personal project of "Tita", aka María del Carmen Rosario Soledad Cervera y Fernández de la Guerra, Dowager Baroness Thyssen-Bornemisza de Kászon et Impérfalva. It houses her collection of “costumbrismo” paintings, 19th century scenes of typical Spanish life. In museum workshops, children can dress up and play archaic.

The institution claims credit for being "decisive for the dynamization and recovery of this part of the city". Pay to get a sign outside your shop and be part of the Entorno Thyssen, the "Thyssen Environment". The Casa Invisible poaches within the Baroness's cultural preserve.

Malaga has numerous other museums, including rented collections from the Pompidou and St. Petersburg. “Málaga, donde habita el arte” (Malaga, where art lives) is a city slogan. It is nearly as exciting as Frankfurt. For live creative culture, there’s Soho Málaga, “the Art District”, jump-started with street art commissions. We did not visit. I am seeing now why many grafiteros are conducting defacement campaigns against these murals, painting it over and sloganizing against them.

(In Occupation Culture (2015), I noted an early appearance of this antagonism in Copenhagen against a work by Shepard Fairey. Of course, Fairey also has a huge mural in Malaga.)

Nothing to See Here

I spent the better part of my life in the artworld, and really, most museums are boring. They’re like a sere desert landscape; nothing grows there. The more of them there are the more boring they become. What is exciting, interesting and stimulating is the artistic environment. That for the most part is not a touristic scene. La Casa Invisible is a creative environment. Not only art (wall paintings, mostly) but artists and projects in progress are to be found there.

As static displays of ostensibly lovely things, museums do one key thing in the touristic city – they underwrite consumption. In the winding streets of Malaga this urge to valorize the tiny expensive shops encrusting every street with a museal air is nearly pathetic.

The metastasizing landscape of consumption creeping into every corner of the touristic city is a process, signalled in William Carlos Williams' poem of 1920 by the line "the pure products go crazy".

Ethnographer James Clifford explains: "If authentic traditions, the pure products, are everywhere yielding to promiscuity and aimlessness, the option of nostalgia holds no charm. There is no going back, no essence to redeem."

Baby Picasso has nothing to tell us

So where is the real? Where is the active culture in Malaga? For most tourists, footsore and pained in the wallet, I’ll guess this is a moot question. For the "malagués", it matters more. If serving indifferent passing lumps of flesh fulfills you, the touristic city is the place to be. If you have some idea of developing another kind of life, maybe you’d drop in on a place like the Casa Invisible.

NEXT: A movie show and a fascist rally; a pass through the Casa Azul; and the last meeting at the Casa Invisible.

LINKS

INURA Málaga 24

https://www.inura24.org/

Moore and Smart, eds., Making Room: Cultural Production in Occupied Spaces (2015)

has a text on the Casa Invisible. Free online --

https://archive.org/details/making_room

Picture: from W. Parker Bodfish, Through Spain on donkey-back (1883). An example of the early form of elite adventure tourism in Andalusia

https://www.loc.gov/item/04005109

Soho Málaga - the “Art District”

https://malagaadventures.com/soho-art-district/

A.W. Moore, Occupation Culture : Art & Squatting in the City from Below (Minor Compositions, 2015)

PDF -- https://www.minorcompositions.info/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/occupationculture-web.pdf

introduction to James Clifford's The Predicament of Culture (1988), "The Pure Products Go Crazy"

at: https://www.writing.upenn.edu/~afilreis/88/clifford.html

Your blogger visits Malaga for the INURA meeting, hosted in part by the Casa Invisible social center. We learn about the city of "sun and sand", and its self-identification as a touurist paradise. Baby Picasso appears as a prominent ghost, promoting the city's many banal museums.

Arriving by train in Malaga for a meeting of urbanists, I taxied straight to the Casa Invisible. I had visited the venerable occupied social center in that touristic city briefly almost 10 years ago. La Casa was closed then, but a friend of a friend of a judge let us in. (The judge, to remain impartial, remained outside.)

La Casa Invisible then was clean, well-tended, with a lovely Andalus-style interior courtyard. I recall a tiny bookstore set into the front of it. A text about the Casa was included in our 2015 book Occupation Culture (Other Forms & JoAAP).

The social center is set amongst the narrow streets of the city’s historic district, so the taxi could only take me near the back door. A press conference for the INURA meeting I had come for was in progress.

A Different Kind of Convention

INURA is the International Network for Urban Research and Action, “people involved in action and research in localities and cities.... activists and researchers… who wish to share”.

This wasn’t really an academic meeting, although it had many of the earmarks. Originating among Zurich-based researchers, the group has been meeting in cities around Europe for decades. They learn about urban spaces through guided tours, then head to a days-long retreat to chat amongst themselves.

I went on some tours with the INURAistxs, and chatted with several of them. I did not go on the retreat.

It was a strain. I’d just returned from a month in the States and had a surgery scheduled. I fell heavily in the school of architecture, which took me out of sessions for a day. The next day I blew a mental fuse and sat insensibly during the meetings.

Despite the rigors and accidents of senior travel, this visit was imiportant to see the Casa Invisible in its ambience. I learned something about this important Spanish social center which improbably maintains itself in a city with a right-wing government cemented in place.

“Sun and Sand”

Malaga is on the southern Mediterranean “Costa del Sol”. The city and the region has been all about tourism for a long while. A main theme of the meeting then was the figuration of the city and its region through that industry. As we found, that conception is getting pretty ragged.

The Costa del Sol is the poster child of excessive overdevelopment. Long one of the more picturesque and oft-depicted parts of Spain, the region was developed as a fountain of foreign currency for the Franco dictatorship. The picturesque white villages of the Andalusian coast were drowned in a tsunami of development – mainly apartment buildings – which has never stopped. Today 30% of Spain’s economy derives from tourism.

(While Costa del Sol is rife with foreigners, I’ll note that in most parts of Spain the tourism is internal, by nationals who want to know their own highly diverse peninsula.)

Tourism for this region was meticulously constructed on top of local traditions and features of Andalusian culture. An RTVE production of the epoch, "Malaga and the Costa del Sol in 1976", on YouTube praises the "organized paradise" – jet airplanes, lavish buffets, bulls, flamenco, titty shows and lots of blonde white people. Over 40 years on, that local flavor seems to have almost entirely evaporated.

Once a Village, Torremolinos is Towers

The two INURA tours I went on focussed on the model touristic city – Torremolinos, just outside Malaga -- and on the museumification of Malaga itself.

The bus from the hostel in Malaga to Torremolinos let us off by a fast wide street sunk into a canyon of high-rise apartment buildings. We walked along this stinky road until we reached the “historic center” of the former town.

Not so long ago, this was a poor part of Spain. In ancient times, the Romans never recreated here; there are no villa sites to excavate. For them, this coastline was industrial, the site of a number of factories of the fermented fish sauce called garum.

In 75 years this town of truck gardens and subsistence fishing went from 4K to 70.4K inhabitants, 40% born outside of the province. There is in the Malaga region a kind of cosmopolitanism, albeit heavily ghettoized, and riven with new mafias and new modes of corruption.

Our two guides for "Torremolinos: The origins of the touristic attraction", Enrique Navarro Jurado and Mario Blanco Vilches, circulated a paper (not online) in which they distinguished phases in tourism -- the "romantic visitors" of the 17th to 18th centuries; early 20th century elite visitors; the "boom" of mass tourism from 1960-73 after the "sun and sand" model; through 1980 a rising demand among the Spanish themselves; finally, a recalibration of the region as urban. Today the aim is "urban development of the Costa del Sol, formed by Torremolinos, Benalmádena and Fuengirola, as a continuous urban, almost a linear city".

The town cum city’s self-understanding, our guide said, is as the embodiment of “the culture of relax”. In the beginning, the canonical urbanist Henri Lefebvre visited, cupped little fishes in his hands along the beach and proclaimed Torremolinos “paradise”. The favorable micro-climate is changing planetarily now, as the summers get hotter, and the beaches need more post-season renovation.

We walked through a ‘70s-era development, the Pueblo Blanco, built like a fake Andalusian village. The white village style is more Californian-inspired than Andalucian. These chockablock apartments are studded with spolia from demolitions in the towns around Malaga.

Way Down Below She May Be

We paused at an overlook, the site of many postcards. Far below the beach and its furnishings spread out. It was dizzying. I did not descend the elevator to see. On one side below us we saw restaurant row. Those had been the fishermens’ houses along the beach where they’d pull up their boats in years past.

Our guide pointed out a modernist structure slated for demolition. In Malaga, historic buildings can be defended against the forces of development, but these efforts are mostly in vain. In part this is because, “every epoch has its imaginary”. Young people now wish to preserve other buildings linked with their childhood memories. These include some of the earliest high-rise tourist apartments.

Through all this, my emotions intervened. I hate cars, and one of the major early developments here was a highway along the beach. To me this kind of environment is a hellscape. It takes a big effort of sympathy to imagine what kind of people thrive within it. But many do, some even against the civic grain.

Baby Picasso in Malaga

I went on two city center tours, the first with our host Kike España from the Casa Invisible, and the artists Rogelio López Cuenca and Elo Vega. “The city of attractions. Urban «development» through the spell of musemification” focussed on the branding of Malaga as the birthplace of Picasso. He lived there as a child.

Screen grab from the YouTube video, "Malaga and the Costa del Sol in 1976"

Art installation of Rogelio López Cuenca, "Casi de todo Picasso" (2011) (Almost everything Picasso)

https://www.arteinformado.com/galeria/rogelio-lopez-cuenca/casi-de-todo-picasso-28563

I visited the Picasso museum in Malaga 10 years ago. It had opened in 2003 in the Juderia, the old Jewish quarter. It's a grand medieval palace which used to be the fine art museum. (That collection was moved.) What I saw there then was mostly the less exciting later work, nice but meh. Picasso’s most influential work is in other towns, like NYC and Zurich. Malaga gave his estate a free insured warehouse.

Our tour began at the artist’s birth house. That is near where the museal center city ends, and the low-rise working class Lagunillas barrio begins. (This site was part of another tour on urban displacement, “a walk through the unacceptable”.)

In 1891, at 10 years, the family left for La Coruña, and later Madrid. On a return visit to Málaga Picasso sought to borrow money from a relative. (No luck.) His formation as an artist took place in Barcelona. In 1934 he left Spain for good, refusing to return while Franco was alive. He parked his great painting Guernica in NYC. (Franco is long dead, and the artwork is back in Madrid.) Picasso was a communist, a part of his biography which is not

celebrated in Málaga. So tourists are basically walking through the Málaga of baby Pablo, as yet uninfected with problematic modern ideas.

Our artist guide, Rogelio López Cuenca, spoke of recent backward-looking architectural modifications to the plaza where the birth house sits. “To memorialize Picasso with reactionary aesthetics is a kind of revenge” on who he was – internationalist, communist, expatriate. And modernist; his engagements with post-impressionist decadence, cubism, and surrealism are not part of baby Picasso’s story. This, our guide said, was the “Malaganization of the fable of Picasso”.

“As if I Were He”

The malagueño Antonio Banderas portrayed Picasso in a TV series (Genius: Picasso 2018). He is prominent in museum openings in Malaga, acting “as a kind of medium for Picasso”.

Rogelio pointed out that the great medieval Alcazar of Malaga was destroyed by Napoleon’s troops in the early 19th century. In 1940 it was reconstructed for touristic purposes. The Roman theater, covered by an office building, was also reconstructed. The recent Museo Carmen Thyssen is the personal project of "Tita", aka María del Carmen Rosario Soledad Cervera y Fernández de la Guerra, Dowager Baroness Thyssen-Bornemisza de Kászon et Impérfalva. It houses her collection of “costumbrismo” paintings, 19th century scenes of typical Spanish life. In museum workshops, children can dress up and play archaic.

The institution claims credit for being "decisive for the dynamization and recovery of this part of the city". Pay to get a sign outside your shop and be part of the Entorno Thyssen, the "Thyssen Environment". The Casa Invisible poaches within the Baroness's cultural preserve.

Malaga has numerous other museums, including rented collections from the Pompidou and St. Petersburg. “Málaga, donde habita el arte” (Malaga, where art lives) is a city slogan. It is nearly as exciting as Frankfurt. For live creative culture, there’s Soho Málaga, “the Art District”, jump-started with street art commissions. We did not visit. I am seeing now why many grafiteros are conducting defacement campaigns against these murals, painting it over and sloganizing against them.

(In Occupation Culture (2015), I noted an early appearance of this antagonism in Copenhagen against a work by Shepard Fairey. Of course, Fairey also has a huge mural in Malaga.)

Nothing to See Here

I spent the better part of my life in the artworld, and really, most museums are boring. They’re like a sere desert landscape; nothing grows there. The more of them there are the more boring they become. What is exciting, interesting and stimulating is the artistic environment. That for the most part is not a touristic scene. La Casa Invisible is a creative environment. Not only art (wall paintings, mostly) but artists and projects in progress are to be found there.

As static displays of ostensibly lovely things, museums do one key thing in the touristic city – they underwrite consumption. In the winding streets of Malaga this urge to valorize the tiny expensive shops encrusting every street with a museal air is nearly pathetic.

The metastasizing landscape of consumption creeping into every corner of the touristic city is a process, signalled in William Carlos Williams' poem of 1920 by the line "the pure products go crazy".

Ethnographer James Clifford explains: "If authentic traditions, the pure products, are everywhere yielding to promiscuity and aimlessness, the option of nostalgia holds no charm. There is no going back, no essence to redeem."

Baby Picasso has nothing to tell us

So where is the real? Where is the active culture in Malaga? For most tourists, footsore and pained in the wallet, I’ll guess this is a moot question. For the "malagués", it matters more. If serving indifferent passing lumps of flesh fulfills you, the touristic city is the place to be. If you have some idea of developing another kind of life, maybe you’d drop in on a place like the Casa Invisible.

NEXT: A movie show and a fascist rally; a pass through the Casa Azul; and the last meeting at the Casa Invisible.

LINKS

INURA Málaga 24

https://www.inura24.org/

Moore and Smart, eds., Making Room: Cultural Production in Occupied Spaces (2015)

has a text on the Casa Invisible. Free online --

https://archive.org/details/making_room

Picture: from W. Parker Bodfish, Through Spain on donkey-back (1883). An example of the early form of elite adventure tourism in Andalusia

https://www.loc.gov/item/04005109

Soho Málaga - the “Art District”

https://malagaadventures.com/soho-art-district/

A.W. Moore, Occupation Culture : Art & Squatting in the City from Below (Minor Compositions, 2015)

PDF -- https://www.minorcompositions.info/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/occupationculture-web.pdf

introduction to James Clifford's The Predicament of Culture (1988), "The Pure Products Go Crazy"

at: https://www.writing.upenn.edu/~afilreis/88/clifford.html

Thursday, April 25, 2024

“Zuri Burns” – A Sift Among the Ashes

Cover of a multi-DVD set about the Zurich occupation movement

I was afraid of Zurich. I passed through the airport years ago on a two-leg flight. The border agents contemplated deporting me for Schengen over-stay, even though I was on my way to the USA. I paid $50 for lunch. Saw the private jets parked in a line on their own runway. Spied some of the beautiful people strolling by. “This is another world,” I thought, and it’s not mine.

But I really wanted to learn about the intense squatting and occupation movement of the 1980s that gave rise to the Rote Fabrik cultural center, and the people who fought so hard against the police in the private banking capitol of Europe.

So we went. Yes, it’s expensive, but you can catch a meal in a box at the Coop supermarket and eat it on a bench by the river. And if you figure out the tram system you can swing around the city like a monkey through the trees. In short, it’s doable. Plus I bought a cool used raincoat for 15 francs.

The story of the Zurich squatting movement offers an important urban model of motivated popular development. And it’s still happening.

The movements which began with a bang in Zurich in 1980 have had two important outcomes – the Rote Fabrik cultural center, and the Kraftwerk 1 cooperative housing development. Squatting is ongoing, with new occupations popping up regularly. The artists, the punks, and the working classes all have a good chance in Zurich at what they call “social luxury”.

I only met a few people, and I wasn’t an energetic ethnographer. But the visit did clear up one strong misconception I have held.

Forget New York

Ten years ago, in Occupation Culture, I proposed the "New York model" of a squatting movement in which artists played a central role. This was against (or with) the assumption that politicals alone do effective squatting.

After my visit to Zurich I can see that the model of occupations driven by culturally-engaged people is a general one, not at all special to NYC. You can indeed create the conditions in the city in which you wish to live. You simply need a little more of what Matt Metzger once called “sand”. (And be ready to sacrifice your NYC “real world” career.)

The squat-based cultural scene in NYC is static. There have been no new actions of public building occupation since the wild ‘90s, and some of those that existed are legalized. The management of the few tiny cultural institutions that came out of it, and the valorization of their legacies are sustained by the work of a handful of aged activists.

The Zurich scene, like that in Madrid where I live, is multi-generational. New occupations are driven by young people who are working within a well-defined tradition with an intelligent set of playbooks and creative tactics.

Not So Cold, but Everything Closed

I picked a bad time to visit. The weather was nice, though. Like everywhere now, spring came early. The forsythia were blazing yellow along the banks of the Limmat, and we didn’t need our heavy jackets. But it turned out the Shedhalle, the contemporary art section of the Rote Fabrik cultural center, was closed for reconstruction. The two major left infoshops, the Fermento and the Kasama were also closed.

I just missed crossing paths with expat squatter artist and musician Peter Missing (#petermissing), who offered to take me to the “post office squat”.

So I parked for a few days in the Sozialarchiv, a small palace of study to see what I could make of the movement I had assumed was definitively in the past.

Image from a period journal from the K-set archive

The movement, as it turns out, is very well historicized. A tremendous five-CDROM set of videos explains the Zurich movement from the ‘60s through the ‘80s over eight hours of video and narration. This is built off the archives of efficient and energetic street media collectives back in the day. Hausbesetzer-Epos: allein machen sie dich ein (2010) is an effective and affecting overview.

One of the librarians kindly gifted me an extra copy she had of the basic history of the movement, Wo-Wo-Wonige (2006). And I picked up a copy of a recent history of the Rote Fabrik Bewegung tut gut – Rote Fabrik (2021) at the cooperative bookstore in the Volkshaus. So I have plenty to chew on with my limited German.

It will take me a time to absorb it.

The Red Factory

I did wander the Rote Fabrik during a rainy weekday when it was all but deserted. The Shedhalle art exhbition and event space – (to call it a “museum” is wrong; it’s more like a cultural generator) – was under renovation. It was full of scaffolding and workers. The cafe was locked up. A few men were working setting lights in the theater, a well-appointed space painted black which adjoined a small bar room.

I wandered the corridors. The stairwell is decorated with posters of past events. All the studios were closed. In a classroom space with windows overlooking the yard I saw the backpacks of the young people who looked out curiously at me as I passed the printing studio. They were receiving a lecture there.

The Fabrik is on the edge of the lake. There’s a dock; in fact there’s a ship-building workshop and a boating club. Surely a pleasant place in the summertime.

A Bit’o bolo-bolo

As for the huge cooperative housing project recently constructed, I did not visit, nor even learn about it until later. Comrades from NYC are well acquainted with the Swiss urbanist Hans Widmer who strived to imagine a “anti-capitalist social utopia”. His “bolo” concepts are reflected in the Kraftwerk 1 development.

I didn’t get to see Kraftwerk 1. Widmer’s publisher (and also mine) was to visit just after me, and he and his partner stayed there. (Blogger turning green.) Miguel Martinez, my onetime comrade in our late squatting research group SqEK, also visited last year as part of the INURA conference. They gave him the 10-cent tour, and he produced a reflection on his visit, a text called “Social Luxury”.

In Kraftwerk 1, individuals have small rooms, sleeping spaces, and access to large common areas like kitchen, living rooms, library, and laundry. This is the format of the Ganas commune in NYC where I lived for some months. Ganas had TV rooms in its different houses, as well as music rehearsal and media production rooms. And a swimming pool.

The housing cooperative includes a food depot linked to a garden coop, a rural link Widmer considered vital for his urban bolos.

Miguel maintains that Kraftwerk 1 living “provides happiness” through increased social life. This is a project, and requires work; living in common is demanding. I recall the strong centripetal force of the Ganas commune. No one really wanted you to leave, to spend your day outside the compound.

He writes of “communal social security” during moments of crisis, and the general support in all the mundane tasks of living, especially childcare. This is a true thing which I have observed. Commune babies are famously self-reliant people, full of confidence and unafraid of the most precarious of life strategies – being an artist.

Despite the great advantages of this mode of living, it is not for everyone. It can be hard work. Ganas spent a lot of time on conflict resolution, and the magazine Communities devotes a lot of space to the question.

Overall, conceptions and realities of “social luxury” both are over-shadowed by a world in which we are endlessly treated to visions of private luxury. The sense of perpetual dissatisfaction that motivates so many aspects of life under capitalism can make even a utopia seem like a drab and confining place.

Not to me.

Writing about this now, and thinking back on my brief time in Ganas makes me sad and envious. Sad that so few of us can have these expanded possibilities in our lives, and envious that, despite the present luxurious fulfilment of my materials needs, I am among the excluded.

Well, I’ve dipped my toe into the Zurich experience here, and there’s a lot more to come. Those Swiss are clever, and have indeed figured a lot of things out that many in Europe and USA could learn from.

LINKS

Midnight Notes, “Fire and Ice: Space Wars in Zurich”

The original brilliant description of the movement, including their innovative tactics

https://theanarchistlibrary.org/library/midnight-notes-fire-and-ice-space-wars-in-zurich

Schweizerisches Sozialarchiv

https://www.sozialarchiv.ch/

Doris Senn, Mischa Brutschin, Hausbesetzer-Epos : allein machen sie dich ein (2010)

https://scholar.archive.org/work/n4fp4q6ghnexhn3ynw7qvcuvpq

T. Stahel, Wo-Wo-Wonige! Stadt- und wohnpolitische Bewegungen in Zürich nach 1968 (2006)

Internet Archive Scholar

https://scholar.archive.org › access › https: › eprint

Interessengruppe Rote Fabrik (Hg.), Bewegung tut gut – Rote Fabrik (2021)

Martínez, Miguel A. (2023) On social luxury. Some reflections resulting from the INURA meeting, Zurich, 2023.

https://www.miguelangelmartinez.net/?Social-luxury

p.m. (Hans Widmer), bolo’bolo (2011, 1984, Autonomedia)

INURA – 2023 – Zurich -- International Network for Urban Research and Action

https://inura23.wordpress.com/

Kraftwerk1

https://www.kraftwerk1.ch/

An ETH Zürich design studio project from spring, 2023, explicates Hans Widmer's ideas and Kraftwerk 1 --

https://topalovic.arch.ethz.ch/Courses/Student-Projects/FS23-Bolobolo-Utopia-Within-Reach

Communities magazine, formerly published by Foundation for Intentional Community, which maintains a global directory of collective living projects at https://www.ic.org/

Onetime squatter artist Ingo Giezendanner, aka Grrrr, holds one of his meticulously drawn books. They'll be at the Allied Productions booth at this year's NY Art Book Fair, as Ingo has visited and worked at Petit Versailles

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)