Friday, December 30, 2022

Germany in Autumn #3: The “Trout Farm” and the Free Party Scene in the ‘90s

Image from the anti-gentrification street opera "Laura Tibor"

Third post from my recent German trip to research the effects of the squatting movement in Berlin and Hamburg. What matters now is archival stuff – the famous “Queeruption” squat of the Tuntenhaus, the epochal free party scene in squatted East Berlin after the fall of the Wall. All of it well remembered decades after its end in museum exhibitions and books. As always now, links are at the bottom of the post.

Repression has capped the squatting movement in Germany. Nothing like the 2021 mini-wave of squatting in Amsterdam seems possible in Berlin or Hamburg. A simmering rage exists against the continually rising price of housing. Recently it was expressed in a protest opera, “Laura Tibor”, a highly produced street production that envisions a socialist utopia… which is definitely not coming to pass.

The exhibition “Tuntenhaus Forellenhof 1990: Gay Communism’s Short Summer” was easily the best recollection of Berlin’s squatting history I saw during this trip. A multinational labor of love, this show at the Schwules Museum recalled the several-month occupation of buildings by gay activists (called “Tunten”, roughly ‘queer’). The brochure (link below) sets the squatting action in the context of the years after the fall of the Berlin Wall – called die Wende, when East German anarchists and their Westie comrades squatted in the Friedrichshain district.

Tunten at play, 1990. Photo by Michael Oesterreich

1990 was a moment of hope for the left – (Nelson Mandella was freed, the US-backed Nicaraguan “contras” surrendered) – and growing fear among gays – (Keith Haring died of AIDS in February; retroviral treatments don’t come along until ‘96). Berliners were seized by a sense of euphoria at the possibilities. Adventures began.

The Tuntenhaus occupations grew to 12 buildings on Mainzer Strasse after May 1st of that year. The squatters named it the Forellenhof (“Trout Farm”). Predators lurked; Nazi skinheads squatted buildings as well, and carried on a lethal gang war against the Tunten.

During this wild interregnum, before the two Germanys were integrated, Tunten met and breakfasted in a common room recreated in the exhibition. This heart of communal life was built as a set after a few moments in the documentary film. “The Battle of Tuntenhaus” (1991) was made by queer US filmmaker Juliet Bashore. The film shows the strong community of differently loving people, and the threats they face, including “everyday fascism”, the hatred of many neighbors. And street fights.

The era is evoked in the Schwules installation: “to ward off the expected nazi attacks, there were homemade shutters of fine-mesh chicken wire…. A typewritten telephone tree was stuck on the wall, for the ever-menacing emergency.” Details were added by participants who remain alive. (Among them is the photographer Wolfgang Tillmans, recently celebrated at the NYC MoMA.)

Tuntenhaus dining room reconstructed at Schwules Museum

Library, bookstore, cafe, bar, communal houses – definitely Autonomen. What in the end was an entire squatted street with a dozen houses was evicted in an epic street battle. The state, as predicted, had ended it.

“It” was a realization of communist ideals by a bunch of queers. Curator Bastian Krondorfer writes, “communism – queer or otherwise – is like a shy deer. Sometimes it appears in a lonely clearing at dusk, before we pick it up, it has disappeared into the thicket of the forest.”

For the exhibition, discussion events returned Juliet Bashore to Berlin. SqEK comrade Andrej Holm, onetime Berlin city housing minister. The “trout farm” and the many other squatted communities throughout Berlin during the late 20th century is a history taken very seriously today.

After the evictions, many Tunten moved to Kastanienallee 86, with its metal "facade exhibition" reading "Capitalism standardizes, destroys and kills”. The Tunten met again in the cellar nightclubs of former East Berlin. It was in these dives, holes and palaces that techno dance music arose, another key outcome of the culture of the squatting movement.

In considering the after-effects of squatting in Berlin, a broad view of the movement culture is needful. So I’ll back up now to theory, and say that just as in the time of the Happenings in the 1960s, the form of the art event itself became a creative medium during this period.

In a 2014 interview Neala Schleuning, author of Artpolitik, a book on "social anarchist aesthetics", spoke of Theodor Adorno’s concern that artists stay “aloof of any kind of capitalist aesthetics.” In Adorno’s notoriously twisty conception, the social context of creative production is embedded in the form of art. “The liberation of form,” Schleuning quotes, “...holds enciphered within above all the liberation of society…. form… represents the social relation in the artwork”.

The artwork’s autonomy – its freedom from spectacular capitalist culture – carried “the dream of revolution into art and into the confrontation with contemporary society”.

Book cover ("Dream and Trauma") shows the aftermath of the Mainzerstrasse evictions

This became clear for me in reading artists’ texts from the catalogue of the 2013 show “Wir sind hier nicht zum Spaß!” (We’re not here for fun), focussed on collective and subcultural structures in Berlin in the ‘90s. (I copied the English translations from the book at the NYiB library; artists weren’t identified in those, so I give the page numbers.)

The Tuntenhaus was the more raucous and spectacular part of a vast and variegated cultural landscape in Wende Berlin. For the animators of that free party scene, Berlin was an urban landscape in which authority was temporarily confused. Suddenly and unexpectedly unified, Berlin was “two very strange halves” (p. 128). With so many abandoned buildings in the East ripe for inhabiting, there was a feeling that this city was where it was happening in western Europe.

Crews of artists began to throw psychedelic parties in industrial wastelands, working with music, light, images and more. Their tactic was, “we throw an illegal party somewhere.” “It was the summer when almost anything seemed possible. The Western system wasn’t yet imported in the East, and the Eastern system had fallen apart completely”.

There were huge empty apartment buildings open for squatting, most with public spaces. Allowed to continue, the squatted streets “could have evolved into something like Christiania in Copenhagen – or perhaps something completely different” (p. 129).

As state-run factories closed down, immense stores of materials and machines became available. One artist scored 50,000 glass lamp tubes and made “techno chandeliers”. They later opened a shop with all their scavenged booty, the Glowing Pickle (p. 130).

One U.S. artist present during those days, Christine Hill, applied the same procedure to the residues of a business in Soho,NYC. Her “Volksboutique Small Business” took up the remaining inventory of my favorite classic old stationery store, Joseph Meyer. She then ‘inhabited’ the stuff in art gallery installations.

‘Shebeens’ and impromptu bars popped up all over Berlin during the ‘90s. “This attitude of squatting places,” one artist wrote, “of not using an already available location but transforming some unknown place by improvising a bar and a PA for just one night – that was the mixture that electrified us. Our motto was: ‘Pop up and vanish!’” (p. 132).

“At the same time, money was not an issue at all. It was always spent for the cause – to keep the luxury alive, which we ourselves have created” (p. 133).

Photo by Mattia Zoppellaro from an article on the free party scene of Berlin in the '90s at huckmag.com

This isn't the "fully-automated luxury communism" of accelerationist "Lenin-goes-to-Silicon-Valley" types. It's a no-rent utopia that actually existed in a momentary vaccuum of capitalist control.

With the turn of the century the free party scene, like the squatting scene, came to an end with a return to order along Western capitalist lines. Squats were evicted. Buildings were sold off and flipped, and stiff rents imposed. Big business started to sponsor the free parties. “From a group functioning without money it changed into who’s important in the new game? Who should you kiss up to in order to become important, to finally make money with what you’re doing?” (p. 142).

Profiteers can’t keep their fingers off of fun. (Are nightclubs even possible without mobsters?) This is the same dynamic of appropriation Aja Waalwijk reported happened to the free festivals organized by groups in Amsterdam in the early 1970s. (See "On Nomads and Festivals in Free Space", House Magic #4 Spring 2012).

Perhaps the fate of the commercialized techno music rave culture is symbolized by the Love Parade. It began in Berlin's open space in 1989, became massive, and ended in 2010 with a crowd crush disaster in Duisberg. Just this year it has partially returned in July with the Rave the Planet parade in Berlin. Billboard reported that long-time organizer, the DJ Dr. Motte, “called for an unconditional basic income for artists and for Berlin’s club culture to be listed as intangible heritage by UNESCO, the U.N.’s cultural agency”.

UBI for artists only? Why not for everyone? To unleash widespread popular creativity and civic consciousness, free from the enforced discipline of labor, aka wage slavery. The Institute of Radical Imagination, based in Italy, has proposed just that in their "Art for UBI (Manifesto)”. For when parties become free again in a post-work world.

LINKS

“Oper über Gentrifizierung in Berlin,” 2021 – performed on the street

https://taz.de/Kunst-gegen-Gentrifizierung/!5774848/

Der Protest Oper film, 2022

Die Oper gegen den Ausverkauf der Stadt!

https://www.lauratibor.de/

Michael Oesterreich(?), "Tuntenhaus Forellenhof 1990: The most anarchic summer Friedrichshain has ever seen", 19 October 2022; by a participant

https://www.exberliner.com/berlin/tuntenhaus-forellenhof-1990-anarchic-summer-friedrichshain-schwules-museum/

PDF of the Schwules Museum’s comprehensive “Tuntenhaus” brochure (ENG & GER):

Broschuere_Forelle_A5_44c_32S.indd – Final_Broschuere_Forelle_A5_44c_32S

Juliet Bashore, "The Battle Of Tuntenhaus Parts I & II" (1991; 45 min.)

https://archive.org/details/BattleOfTuntenhausPartsIII

Geronimo, Fire and flames: A history of the German autonomist movement, 5th edition, 1997/translation PM Press, 2012

https://pmpress.org/index.php?l=product_detail&p=310

free download – https://libcom.org/article/fire-and-flames-history-german-autonomist-movement

Christine Bartlitz, Hanno Hochmuth, Tom Koltermann, Jakob Saß, Sara Stammnitz, Traum und Trauma. Besetzung und Räumung der Mainzer Straße 1990 in Ost-Berlin (2020); this is not the only book on the subject

https://www.christoph-links-verlag.de/index.cfm?view=3&titel_nr=9104

Tuntentinte (queer ink) blog, named for the ‘90s zine

https://tuntentinte.noblogs.org/wtf-is-tuntentinte

Blog of the Tuntenhaus at Kastanienallee 86

https://www.kastanie86.net/

catalogue of exhibition, “Wir sind hier nicht zum Spaß! Kollektive und subkulturelle Strukturen im Berlin der 90er Jahre”, Kunstraum Kreuzberg/Bethanien, 2013.

https://www.kunstraumkreuzberg.de/publikationen/wir-sind-hier-nicht-zum-spass/

Aja Waalwijk, "On Nomads and Festivals in Free Space", House Magic #4, Spring 2012

Online as: house-magic-4.pdf – [Squat!net], and elsewhere

Love Parade

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Love_Parade

"Art for UBI" (Manifesto) is a platform around on the role of art and art workers in the struggle for social justice and a transition towards post-capitalist forms of life

https://instituteofradicalimagination.org/2022/09/17/art-for-ubi-manifesto-book-launch/

Monday, December 12, 2022

Germany in Autumn #2: Picking Amongst the Textual Ruins

"No Power for Anyone" -- cover of the Ton Steine Scherben songcomic

This is the 2nd post in the account of my visit to Germany in Fall of 2022. I’m looking for the traces of squatting in EU cities, returning to the trail I followed in my work with the SqEK group from 2009 to 2016. In this I tell of my visit to a squatted institution in Berlin, the search for Peter Missing, and rave geek Tobi’s big new book “Please Live”. I connect with old artist comrades Wolfgang Staehle and Philip Pocock, and ruminate about others.

For my second day of research in Berlin, I visited a comrade living in the old Bethanien hospital complex. Among its several projects, NYiB houses a Collective Library and poster archive. There I learned of some important recent books and historical exhibitions that have come along since I last paid attention.

New Yorck im Bethanien adjoins the Georg Rauch Haus, one of the earliest Berlin squats. They have their own song – "Hau ab: Rauch-Haus-Song" ("Get lost”; “Das ist unser Haus!") by the band Ton Steine Scherben. The band is beloved, and I picked up a graphic comic book done around their lyrics. When I passed by, the Rauch Haus was still very colorful with its graffiti slogans and encrustations of political posters.

It’s tricky to get hold of comrade X. He asked me to install Signal, an encrypted messaging app. This wasn’t so easy, but it was worth it, an excellent meeting in which X showed me several important sources.

“Comms” in general on this trip turned out to be quite a problem. Expat U.S. artist Peter Missing only uses Facebook messenger. I don’t have FB on my cel phone. We set up an appointment to meet, and Peter wasn’t there. “Something came up…” It was a trek out there, and fruitless. I tried to catch him on the swing back from Hamburg to the airport in Berlin. Again, no dice. “Today I realized I have to be at a funeral.”

Peter Missing is the squatter artist par excellence. He was in the thick of the movement in NYC in the ‘90s, fronting a band called Missing Foundation notorious for a graffiti slogan of an upside-down martini glass and the epigram “Party’s Over 1933”. Later he moved to Hamburg, where he also squatted. (I saw his martini-glass tag there in 2010.) I last saw him in the yard of Kunsthaus Tacheles, the giant Berlin art squat before it was evicted in 2012. Ten years on, Peter Missing is painting large-scale murals in his dense colorful jigsaw puzzle style. He did one recently for the Berlin Urban Nation street art museum. Finally, he said, “mail me your questions”.

(A recent screed of his is stuck at the end of this blog post.)

Comrade X showed me his recent essay in Rebellisches Berlin: Expeditionen in die untergründige Stadt (Gruppe Panther, 2021). He also had the book Tacheles: Die Geschichte des Kunsthauses by Stefan Schilling (2016), which is o.p.. The Urban Nation library couldn’t find their copy when I visited in spring.

The biggest book find at NYiB was Bitte Lebn (Please live), a new fat tome edited by Tobias Morawski. I met Tobi when he did Reclaim Your City in 2014, a slim book on political graffiti in Berlin. Tobi then was involved in a party-production group called Mensch Meier. I got the idea that he’d given up working on political graffiti and was down for making music business money, like that guy in Amsterdam.

But it looks to be more than that – “We are a venue,” MM write, “A platform. A collective. We are all about grassroots democratic solidarity. We are Mensch Meier. And you are, too, when you are here.” Yes, they do music, and more. The name seems to come from song by the Ton Steine Scherben group, a talkin’ blues about an Everyman. The MM gang is mostly into techno & rave. Their website is splendidly designed.

Rave people and culture played a central role in squatting during the 1990s, a story which, unlike anarcho-punk, remains still to be told. ETC Dee, another SqEK comrade, was a DJ with a free party tribe which roamed Europe during those years.

I had a visit in Berlin with expat Canadian artist Philip Pocock. He’s been posting photos from the early 1980s squatting scene (see my last “Occuprop” post). Philip is still hiding from Covid, but he emerged into the open air for a while to talk. Philip recalled his days amongst the squatters. Some of their buildings fronted directly on the Wall, and they would ‘entertain’ the East German border guards in their towers with public sex acts and rooftop jazz concerts.

Philip is a photographer who has burrowed deep into technical processes. He regaled me with his past art adventures, which included a globe-trotting expedition to survey the equator. One of collaborators he worked with was Wolfgang Staehle, founder of the early online community The Thing.

Image from "AI Realism Qantar" by Almagul Menlibayeva in "The Thing Is" exhibition

When I caught up with him, Wolfgang was in the midst of a new Thing exhibition, “The thing is…”. He and Caspar Stracke hosted me for a book talk about my new memoir (see the related blog: “Art Gangs”). The best part of that was a video jam of old ‘70s and ‘80s cable TV work rescued by the XFR Collective and posted on archive.org. Viel spass!

Berlin buzzes with a multitude of art projects, many riding the border of starkly present political issues. It’s a serious town. In addition to the multi-sited Thing exhibition (I only had time to glance at one of them), I caught a book talk by Jacopo Galimberti on the artists of the Autonomia movement. The meat of his talk was strictly art historical. He had interviewed artists who worked on Autonomist journals, examined their archives, etc. His iconographic analysis connected radical grahics with classical themes, much like the "many-headed hydra", an emblem for the people – the rabble – in revanchist 18th c. discourse.

So far as a classic art historical analysis of the squatting movement artists goes, I can't follow that path, although I hope someone does. Nearly all of the artists who paint in and on the exterior walls of squatted buildings are anonymous. Of course they all have names. This work builds rep for street artists, but it's an underground I don't know. Bitte Lebn may open some doors on this question when I get around to studying it.

For my "Occupation Culture" book (2015) I recounted direct experiences with squatters and squat researchers. This trip I focussed on remnants. There are quite a number of anniversary publications of squat projects which I have yet to sort through. Berlin, like NYC, has been about processing its radical pasts for quite a while now. Opportunities for experiment and innovation when foreclosed still become archival products and events. And tourist attractions.

As for literal remnants of the period – (even exactly what is that? i.e., how to periodize, another classic historical question) – I saw one last giant steel sculpture still standing in Goerlitzer Park. In ‘86 there were many of these monstrous metal constructions to be seen, rising like transformers throughout the park. Where did they go? Were they "squatter art"?

I was told that Josef Strau was set to make a history about them for a show in Berlin in '04 (“Now and Ten Years Ago”, Kunstwerke, Berlin) but he decided against it. That show was also intending to draw a line between NYC and Berlin in the ‘80s and ‘90s. I loaned ABC No Rio materials to it. But the focus shifted (curatorial shit happens), and the catalogue remained unpublished.

Some textual remains sit on Stephan Dillemuth’s rabbit-hole of a website, “Society of Control”. He and Strau worked together on the important artists gallery project Friesenwall 120 in Cologne in the ‘90s, laying the ground work for the genre of the artists research exhibition.

Christine Hill, an artist with Ronald Feldman Gallery, had one of her first shows at Kunsthaus Tacheles, called “Hinter den Museen” (Behind the museums), in 1991. She was an early “services” artist She told me of wandering with her little red wagon amongst the Berlin squats in those days when I sought her advice at her ‘office’ in the gallery.

Tacheles in ruins

Tacheles when I passed it in October. Artists long gone.

On this trip, both Philip Pocock and Wolfgang Staehle told me they knew artists who’d been closely involved in the Berlin squats. More work to do, in my follow-up visits.

This is pulling up threads from a pile of rememberings, like digging through my boxes and coming upon scattered notes that seem to hang together. Artists have taken inspiration from squats, have worked and lived in them, but it’s a thread of art history which hasn’t been picked out – in fact, it’s been suppressed.

Which is why I go on.

NEXT: Tutenhaus and the “Communism of Love”; Hamburg, the “Dangerous Neighborhood”.

LINKS

Collective Library and poster archive at New Yorck im Bethanien

https://kollektivbibliothek.noblogs.org/?p=1894

Tobias Morawski, “Reclaim Your City” (2014) - PDF Free Download

https://docplayer.org/211613562-Tobias-morawski-reclaim-your-city.html

Mensch Meier

https://menschmeier.berlin/en

“Rave”

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rave

Rave culture: “My city: Berlin with Andreas Schneider”, who runs the analogue synth mecca Schneiders Büro in the city. The post includes a video about Schneider's analog synthesizer shop

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/aug/10/berlin-m99-hans-georg-lindenau-corner-shop-revolutionary

Josef Strau

http://vilmagold.com/artist/josef-strau/

NYC texts on Stephan Dillemuth’s website “Society of Control”

http://www.societyofcontrol.com/pmwiki/compstudies/compstudies.php?n=Main.TextsOnline

Martin Beck in conversation with Stephan Dillemuth about the Cologne gallery project Friesenwall 120

http://societyofcontrol.com/outof/sdwiki/pmwiki.php/FW120/BeckDillemuthEn

Christine Hill

https://feldmangallery.com/artist-home/christine-hill

Stephan Dillemuth, "Shnitzelshanke back from storage", image from Society of Control website. The yard of Tacheles is visible in lower left.

“IN THE DEAD CENTER OF BERLIN =oranienburgerstr ==== the old berlin is gone circa 1990 - present ; but the memories are burned into our subconcious / tacheles kunsthaus (photo} /===== and the new berlin is set up to kill culture / and force people into submission / the rents will be the final nail in the coffin .........in this'' capital ''city ....as we all knew in 1990 this time would circle around ...# unfreindly place # dead energy # babies puppies & yuppies # unliveable prices # a place to waste time # only tags survived # sitting in cafes for no reason”

– Peter Missing, Facebook, December 2022

Friday, November 25, 2022

Getting Popular: Back to Berlin, Part One

Poster from Rebel Disorder store -- "Peace to the Huts, war to the Palaces", with an image of Georg Rauch, for whom a famous squatted house is named

Like everywhere these days, the German cities of Berlin and Hamburg were unseasonably mild in early November. I came there after a long time gone to pick up the trail of squatting for a new book project, a dream deferred.

The squatting movement is pretty low now, and nearly sunk in Berlin. You have to sniff like a hound to catch a whiff of the acrid flame of its spirit smoldering beneath the rubble of bourgeois consumption society.

I have in mind now a book on the after-effects, the leavings, the important accomplishments of the European squatting movement in some of its major sites – most of which are long gone.

My first stops on this trip were archives – the Papier Tiger Archiv in the Kreuzberg district of Berlin, and a library in the New Yorck im Bethanien. Moving on to Hamburg, I visited Park Fiction and Gaengeviertel, and failed to find the Rote Flora and its Archiv der Sozialen Bewegungen open. I met a few folks and chatted, and lit the lamp for the German part of my project. A lingering ideology of revolutionary resolve is part of that.

Gone, Gone, Gone

The most salient thing about the famous Berlin squatting movement of the 1980s and ‘90s is its near total invisibility today.

The extent of the old movement can be grasped in the map of “Berlin Besetzt” (Squatted Berlin), which locates and briefly describes most of the Hausbesetzung (squatted house) projects in Berlin in the last several decades.

It was vast. Our research group SqEK (Squatting Everywhere Kollective) was toured through its then-quite-evident remains over 10 years ago.

Squatters in Berlin, 1981. Photo by Tom Ordelman

The streets of Kreuzberg tell the story of today. Great tall kiosks are covered top to bottom with the same commercial posters, kiez after kiez (i.e., barrio). Corporate monoculture and its wage slaves are winning against the ragged hordes of volunteers of yesteryear. And the artists who aren’t stadium-commercial seem to have largely checked out of street communication. Graffiti is plentiful, but it’s aimless pointless name tags.

“When Kreuzberg was wild” (title of an article on a tourist website)

Now, besides colorful stories and the memories of old folks in their co-op apartments, what remains of the movement?

An enormous revaluation of property is what. The Guardian wrote in 2016 that “rents in Kreuzberg were on average the highest in the German capital.” Exactly the same thing happened in “Loisaida rebelde”, NYC. David Harvey was right – rent-seeking is the new basis of capital accumulation in cities today. And first come the squatters and the artists, then come the speculators and developers.

When developers were afraid. "Fire and Flame" in 1981. Photo by Paul Glaser

I began in Berlin by retracing some steps from our SqEK meetings there of long ago. In May I had launched my new book Art Worker in Berlin, and passed by the Regenbogen Fabrik (Rainbow Factory). This early squatted complex celebrated their 40th year in 2021. One can never get a room in their hostel as I’d hoped, but I could see that the principal projects in this live/work complex were still active:

What Is Still Going On at the Fabrik

– A wood workshop, established soon after the occupation of 1981, when the urgent task of restoring squatted buildings was uppermost.

– A bicycle workshop, at one time the largest in Berlin. (The city was a bicycle heaven a decade ago, but that seems to have changed a lot. There's still a morning commute, but bikes on the streets are much less common today, and the many rental spots for tourists have vanished.)

– A cafe, which I was told is open now only one day a week, although on Facebook they say it is reformulating yet again, with migrants as cooks; – A movie theater, the most unusual aspect of the complex, which continues to host regular events.

– the children’s care center – the “kita” – was a key early project, and they still describe themselves as a “childrens, cultural and neighborhood center”.

– I spotted a bookstore setup in a window there, but that was closing and I could not see it clearly.

The Regenbogenfabrik was and is committed to concepts and organizational forms of a “solidarity economy”, a way of living that is proactively anti-capitalist. It’s a public micro-utopia, an important vestige of the squatting movement of the 1980s.

The Papier Tiger Archiv

I had an appointment to visit the renowned Papier Tiger Archiv. This Berlin archive of left movements is where Josh MacPhee and Dara Greenwald collected scans of German political posters for their important 2008 “Signs of Change” exhibition at Exit Art. That show preceded the couple’s founding of the Interference Archive, an active autonomous archive in Brooklyn.

The PT Archiv also houses the library of Kukuck, the Kunst- und Kulturcentrum of the 1980s, but I forgot to ask about it. Although Sarah Lewison contributed photos and a brief text on it from her time there to our anthology Making Room: Cultural Production in Occupied Space (2015: PDF online), what Kukuck was is still vague to me.

“Punx”, who was sitting the archive that day, didn’t seem very jazzed by my project. I wasn’t well prepared. There’s a lot online I haven’t processed, and secondary books which I’ve yet to see.

Philip Pocock's photo of a Berlin squat, 1982

I explained I’m on a search for the residues, the important outcomes of major squatting projects in different European cities. Besides the enormous raises in rent, which I recall led radical Baltimore housing activists to call for the houses of squatters to be attacked, I proposed that bookstores are important cultural artifacts of the squatting movement in Berlin. I got that flash from a photo by Philip Pocock of a Berlin squat from 1982 posted which shows a newly squatted building with an incipient bookstore announcing itself with a banner.

Fumbling Around

We spoke about places like Oh21, where I later ordered the Autonome in Bewegung book which was stolen from me in Philadelphia. I’d bought that a decade ago from a weird street fighters’ gear shop run by a guy in a wheelchair – Hans-Georg Lindenau. He’s a Kreuzberg character, it turns out, whose M99 shop was evicted around 2016.

Oh21 bookshop in Kreuzberg today. Note the posters hanging above the display of books. Posters and other propaganda is distributed via movement bookstores.

The PTA is an important repository of radical left documents. A young woman arrived as I was there to work on the Autonomen.

An artist in our Colab group, Diego Cortez visited Germany in ‘77. He went with Anya Philips to Stammheim prison to try to meet Holger Meins, an imprisoned member of the RAF. Meins had been a filmmaker. He studied alongside Harun Farocki. Diego wanted to interview him for our X Magazine. I learned later that a film was made about Meins – Starbuck Holger Meins, which includes some of his film footage. “Starbuck” because he was the helmsman like in Moby Dick, the strategist of the RAF group.

This is a cross between art and the most extreme left activism. German Autonomen were famed for their fights with cops. Still the book of their history has an oddly whimsical cover image – a masked street fighter seated in a shopping cart – “in movement”.

Joseph Beuys’ engagement with the German Green party before he was purged was also a moment when art and politics crossed strongly. Punx suggested the Green Party archives could illuminate that. That may be a little too far for me to go; the recent epic biography of Beuys is still untranslated.

We talked about the Tutenhaus, the mythical squatted street. And he pointed me to an exhibition “Tuntenhaus Forellenhof 1990: Gay Communism’s Short Summer” still up at the Schwules Museum. I made it there some days later (details in next post).

Social centers, I suggested, were places where working class young people could become involved with cultural activity. Punx laughed at that. He said squatters were middle class people.

That’s something of an open question, I think. I wonder also about alternative kids, commune brats. To what class do they belong?, since their upbringing and schooling etc. removes them a little from the normal runs of class reproduction. Is that a small thing? Miguel Martinez is the only person I know who has interviewed enough squatters to give some kind of answer to this question.

NEXT – New Yorck im Bethanien, Georg Rauch Haus, “Bitte Leben”, Peter Missing and Hamburg-- Gängeviertel and Park Fiction, Vokü at the Haffenstrasse.

LINKS

“Berlin Besetzt” (Squatted Berlin) map of squatted house projects in Berlin

https://www.berlin-besetzt.de/#!id=6

PDFs of my zine, “House Magic: Bureau of Foreign Correspondence” from 2012 and 2013, with records of our German visit can be found here:

https://sites.google.com/site/housemagicbfc/

"launched my new book"

It's a memoir of my years in the NYC artworld: Art Worker: Doing Time in the NY Artworld (Journal of Aesthetics & Protest, 2022)

in paper and e-book at: INS BITLY

“rents in Kreuzberg“

Philip Oltermann, “'State enemy No 1': the Berlin counter-culture legend fighting eviction”, Wed 10 Aug 2016

theguardian.com

Regenbogen Fabrik

https://rbf.otteweb.de/

Papiertiger Archiv

https://archiv-papiertiger.de/index.php

“Signs of Change” exhibition at Exit Art. The full program of this show is on an Italian website:

http://1995-2015.undo.net/it/mostra/75575

Philip Pocock

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Philip_Pocock_(artist)

Lily Cichanowicz, “M99: Berlin’s ‘Corner Shop For Revolutionary Needs’”, 20 December 2016

theculturetrip.com

AG Grauwacke, Assoziation A e.V., , "Autonome in Bewegung: Aus den ersten 23 Jahren" (2003; reprints up to 2020)

http://www.assoziation-a.de/buch/autonome_in_bewegung

buchladen oh*21 - oh21.de

https://www.oh21.de/

"Tuntenhaus Forellenhof 1990: Gay Communism’s Short Summer" at the Schwules Museum, Berlin

https://www.schwulesmuseum.de/ausstellung/tuntenhaus-forellenhof-1990-gay-communisms-short-summer/?lang=en

The M99 shop before its eviction in 2016

Like everywhere these days, the German cities of Berlin and Hamburg were unseasonably mild in early November. I came there after a long time gone to pick up the trail of squatting for a new book project, a dream deferred.

The squatting movement is pretty low now, and nearly sunk in Berlin. You have to sniff like a hound to catch a whiff of the acrid flame of its spirit smoldering beneath the rubble of bourgeois consumption society.

I have in mind now a book on the after-effects, the leavings, the important accomplishments of the European squatting movement in some of its major sites – most of which are long gone.

My first stops on this trip were archives – the Papier Tiger Archiv in the Kreuzberg district of Berlin, and a library in the New Yorck im Bethanien. Moving on to Hamburg, I visited Park Fiction and Gaengeviertel, and failed to find the Rote Flora and its Archiv der Sozialen Bewegungen open. I met a few folks and chatted, and lit the lamp for the German part of my project. A lingering ideology of revolutionary resolve is part of that.

Gone, Gone, Gone

The most salient thing about the famous Berlin squatting movement of the 1980s and ‘90s is its near total invisibility today.

The extent of the old movement can be grasped in the map of “Berlin Besetzt” (Squatted Berlin), which locates and briefly describes most of the Hausbesetzung (squatted house) projects in Berlin in the last several decades.

It was vast. Our research group SqEK (Squatting Everywhere Kollective) was toured through its then-quite-evident remains over 10 years ago.

Squatters in Berlin, 1981. Photo by Tom Ordelman

The streets of Kreuzberg tell the story of today. Great tall kiosks are covered top to bottom with the same commercial posters, kiez after kiez (i.e., barrio). Corporate monoculture and its wage slaves are winning against the ragged hordes of volunteers of yesteryear. And the artists who aren’t stadium-commercial seem to have largely checked out of street communication. Graffiti is plentiful, but it’s aimless pointless name tags.

“When Kreuzberg was wild” (title of an article on a tourist website)

Now, besides colorful stories and the memories of old folks in their co-op apartments, what remains of the movement?

An enormous revaluation of property is what. The Guardian wrote in 2016 that “rents in Kreuzberg were on average the highest in the German capital.” Exactly the same thing happened in “Loisaida rebelde”, NYC. David Harvey was right – rent-seeking is the new basis of capital accumulation in cities today. And first come the squatters and the artists, then come the speculators and developers.

When developers were afraid. "Fire and Flame" in 1981. Photo by Paul Glaser

I began in Berlin by retracing some steps from our SqEK meetings there of long ago. In May I had launched my new book Art Worker in Berlin, and passed by the Regenbogen Fabrik (Rainbow Factory). This early squatted complex celebrated their 40th year in 2021. One can never get a room in their hostel as I’d hoped, but I could see that the principal projects in this live/work complex were still active:

What Is Still Going On at the Fabrik

– A wood workshop, established soon after the occupation of 1981, when the urgent task of restoring squatted buildings was uppermost.

– A bicycle workshop, at one time the largest in Berlin. (The city was a bicycle heaven a decade ago, but that seems to have changed a lot. There's still a morning commute, but bikes on the streets are much less common today, and the many rental spots for tourists have vanished.)

– A cafe, which I was told is open now only one day a week, although on Facebook they say it is reformulating yet again, with migrants as cooks; – A movie theater, the most unusual aspect of the complex, which continues to host regular events.

– the children’s care center – the “kita” – was a key early project, and they still describe themselves as a “childrens, cultural and neighborhood center”.

– I spotted a bookstore setup in a window there, but that was closing and I could not see it clearly.

The Regenbogenfabrik was and is committed to concepts and organizational forms of a “solidarity economy”, a way of living that is proactively anti-capitalist. It’s a public micro-utopia, an important vestige of the squatting movement of the 1980s.

The Papier Tiger Archiv

I had an appointment to visit the renowned Papier Tiger Archiv. This Berlin archive of left movements is where Josh MacPhee and Dara Greenwald collected scans of German political posters for their important 2008 “Signs of Change” exhibition at Exit Art. That show preceded the couple’s founding of the Interference Archive, an active autonomous archive in Brooklyn.

The PT Archiv also houses the library of Kukuck, the Kunst- und Kulturcentrum of the 1980s, but I forgot to ask about it. Although Sarah Lewison contributed photos and a brief text on it from her time there to our anthology Making Room: Cultural Production in Occupied Space (2015: PDF online), what Kukuck was is still vague to me.

“Punx”, who was sitting the archive that day, didn’t seem very jazzed by my project. I wasn’t well prepared. There’s a lot online I haven’t processed, and secondary books which I’ve yet to see.

Philip Pocock's photo of a Berlin squat, 1982

I explained I’m on a search for the residues, the important outcomes of major squatting projects in different European cities. Besides the enormous raises in rent, which I recall led radical Baltimore housing activists to call for the houses of squatters to be attacked, I proposed that bookstores are important cultural artifacts of the squatting movement in Berlin. I got that flash from a photo by Philip Pocock of a Berlin squat from 1982 posted which shows a newly squatted building with an incipient bookstore announcing itself with a banner.

Fumbling Around

We spoke about places like Oh21, where I later ordered the Autonome in Bewegung book which was stolen from me in Philadelphia. I’d bought that a decade ago from a weird street fighters’ gear shop run by a guy in a wheelchair – Hans-Georg Lindenau. He’s a Kreuzberg character, it turns out, whose M99 shop was evicted around 2016.

Oh21 bookshop in Kreuzberg today. Note the posters hanging above the display of books. Posters and other propaganda is distributed via movement bookstores.

The PTA is an important repository of radical left documents. A young woman arrived as I was there to work on the Autonomen.

An artist in our Colab group, Diego Cortez visited Germany in ‘77. He went with Anya Philips to Stammheim prison to try to meet Holger Meins, an imprisoned member of the RAF. Meins had been a filmmaker. He studied alongside Harun Farocki. Diego wanted to interview him for our X Magazine. I learned later that a film was made about Meins – Starbuck Holger Meins, which includes some of his film footage. “Starbuck” because he was the helmsman like in Moby Dick, the strategist of the RAF group.

This is a cross between art and the most extreme left activism. German Autonomen were famed for their fights with cops. Still the book of their history has an oddly whimsical cover image – a masked street fighter seated in a shopping cart – “in movement”.

Joseph Beuys’ engagement with the German Green party before he was purged was also a moment when art and politics crossed strongly. Punx suggested the Green Party archives could illuminate that. That may be a little too far for me to go; the recent epic biography of Beuys is still untranslated.

We talked about the Tutenhaus, the mythical squatted street. And he pointed me to an exhibition “Tuntenhaus Forellenhof 1990: Gay Communism’s Short Summer” still up at the Schwules Museum. I made it there some days later (details in next post).

Social centers, I suggested, were places where working class young people could become involved with cultural activity. Punx laughed at that. He said squatters were middle class people.

That’s something of an open question, I think. I wonder also about alternative kids, commune brats. To what class do they belong?, since their upbringing and schooling etc. removes them a little from the normal runs of class reproduction. Is that a small thing? Miguel Martinez is the only person I know who has interviewed enough squatters to give some kind of answer to this question.

NEXT – New Yorck im Bethanien, Georg Rauch Haus, “Bitte Leben”, Peter Missing and Hamburg-- Gängeviertel and Park Fiction, Vokü at the Haffenstrasse.

LINKS

“Berlin Besetzt” (Squatted Berlin) map of squatted house projects in Berlin

https://www.berlin-besetzt.de/#!id=6

PDFs of my zine, “House Magic: Bureau of Foreign Correspondence” from 2012 and 2013, with records of our German visit can be found here:

https://sites.google.com/site/housemagicbfc/

"launched my new book"

It's a memoir of my years in the NYC artworld: Art Worker: Doing Time in the NY Artworld (Journal of Aesthetics & Protest, 2022)

in paper and e-book at: INS BITLY

“rents in Kreuzberg“

Philip Oltermann, “'State enemy No 1': the Berlin counter-culture legend fighting eviction”, Wed 10 Aug 2016

theguardian.com

Regenbogen Fabrik

https://rbf.otteweb.de/

Papiertiger Archiv

https://archiv-papiertiger.de/index.php

“Signs of Change” exhibition at Exit Art. The full program of this show is on an Italian website:

http://1995-2015.undo.net/it/mostra/75575

Philip Pocock

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Philip_Pocock_(artist)

Lily Cichanowicz, “M99: Berlin’s ‘Corner Shop For Revolutionary Needs’”, 20 December 2016

theculturetrip.com

AG Grauwacke, Assoziation A e.V., , "Autonome in Bewegung: Aus den ersten 23 Jahren" (2003; reprints up to 2020)

http://www.assoziation-a.de/buch/autonome_in_bewegung

buchladen oh*21 - oh21.de

https://www.oh21.de/

"Tuntenhaus Forellenhof 1990: Gay Communism’s Short Summer" at the Schwules Museum, Berlin

https://www.schwulesmuseum.de/ausstellung/tuntenhaus-forellenhof-1990-gay-communisms-short-summer/?lang=en

The M99 shop before its eviction in 2016

Wednesday, October 12, 2022

“Like Ivy Climbing the Walls”: “Giro gráfico” in Madrid

A review of the “Giro gráfico” exhibition at the Reina Sofia museum. (Closed in Madrid; next venue Mexico, D.F.)

The long dark deep pain is unimaginable, near-geological in its duration, the loss of lives, lands, knowledges and futures produced by the colonization of the Americas. Indigenous American civilizations were erased and their existence later denied. All of this we now must recognize and answer for.

Columbus, who started in slaving and massacring as soon as he arrived is the anti-hero of October 12th. A new children’s book features him accurately as an ogre. The unmaking of this hero of Italian-Americans began in earnest during the quincentennial year of 1992. See this pedagogical guide “HOW to '92” produced by the Alliance for Cultural Democracy and posted in full at Gregory Sholette’s “Dark Matter Archives”. The work of de-education continues.

Columbus killed for gold. His crimes, and those of other early colonists, were famously called out in the first decades of colonization of the Americas by the 16th century priest Bartolomé de las Casas.

Today Native Americans are being killed for land, and for fighting to conserve its resources. Over the last ten years, it’s been at the rate of one every two days according to Global Witness. Columbus’ crimes live on in a repetition compulsion of inhuman greed.

In response to that report, Carolina Caycedo writes of these crimes, and their remembrance:

“La siembra, or ‘the sowing,’ is an expression used by communities in Latin America when one of their members, leaders, or elders is killed for their activism in defense of territory, water, or life. They refer to the violent act of killing as the sowing, in order to turn around their loss and understand it through the abundance of the legacy it leaves. The murder of an activist sows a legacy, because the person who is buried—planted, in a manner of speaking—becomes a seed for the ongoing political and organizational processes of the community.”

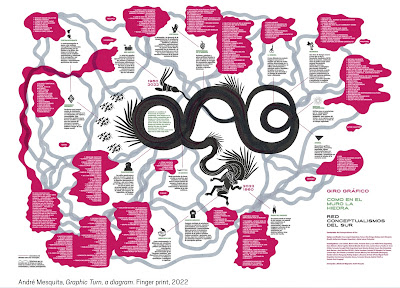

On the last day of the exhibition “Giro gráfico” at Reina Sofia museum – (“Graphic Turn: Like the Ivy on the Wall”) – I returned with the intention of writing about it. I’d been a few times before to this massive display of political art curated collectively by the Red Conceptualismos del Sur, in which André Mesquita played an important role. I was out of town when first Andre, and then Caleb Duarte (more of him and them later) arrived to work on the show in May.

The show is overwhelming, as are so many of the Reina Sofia shows. I honestly couldn’t handle it the first times I went. The cumulative effect on me was so sad and desperate it frightened me. It was a ‘walk among the tombstones’. But this must be observed and reported. Such a depth of pain, such endless unrequited struggle. Sure, progress has been made, but long, long and so very hard, and it doesn’t end, as figures like Bolsonaro recur and insist. The ruthless greedy “fever of Columbus” continues to rage and consume indigenous lands. Nothing seems to stop the plague of killings.

Plan drawn up by Andre Mesquita of the "Gira" exhibition

To think of all this artistic memorial work climbing, as the title has it, like ivy on the walls, ivy a plant that never quits but always climbs – and to think of the dead as seeds planted which grow new generations of resistors is the only comfort available. But comfort isn’t what is needed. Resolution – determination – a firm promise that this struggle be kept always in mind and not forgotten.

For those who fight, it is “ ‘namakasia’ [meaning] both ‘ever strong’ as well as ‘ever forward’ in the Yaqui language,” writes Caycedo (cited above). “It is a tribal cry of encouragement, a collective call to never give up” which she learned from Tomás Rojo Valencia, a Yaqui leader “sown” in Sonora, Mexico, in 2021. He was murdered for demanding the tribe's legal rights to half the water which the governments of Sonora state and federal Mexico were diverting for the needs of corporate clients.

“Giro gráfico” winds through gallery after gallery, in a plan of display that André Mesquita images with a central form of a dragon. The crew from Red Conceptualismos del Sur have been developing this show for years.

[I note here a text that describes the show and that collective process from the inside – Cristina Híjar González, "Giro Grafico: Como en el Muro la Hiedra", 6 junio, 2022, “Breve e incompleta crónica de la exposición internacional de acciones gráficas y visualidades de la RedCSur en el Museo Reina Sofía”. ENG readers can put it into machine translation as I did and it comes out pretty good.]

I entered the Madrid show from the back, past the giant "Mapamundi" made by the mapping collective Iconoclasistas (2019), in which multi-armed god-like peasants illustrate a map of global land ownership.

Detail of the Iconoclasistas "Mapamundi"

The next room is crammed with graphic reminders of the Argentinian dictatorship’s infamous crimes (1974-84). Exiled leftists organized resistance abroad, especially the Paris campaign of AIDA for the “100 Argentine artists disappeared”. That was indeed the ‘tip of the iceberg’, since the killing is estimated to have caught up some 30,000 unfortunates. The demonstrations in Paris went on weekly for 320 weeks, over six years. Since 1996 there has been an annual March of Silence in Argentina for the dead/disappeared.

A great stack of signs dominated the room, each a photo of a murdered person. A documentary film, “Where Are They?” from the archives of Simone de Beuvoir played on a monitor. That is an eternal cry, since, as with the Mexican Ayotzinapa 43, the bodies of the dead are rarely given back. The post office of official death makes no returns, and has no dead letter office.

Ana Longoni explains the show in a brief museum video with ENG subtitles

I discussed all this with a friend who is closely involved with what is called “historic memory” in Spain, i.e., the exhumation of mass graves of people killed during the fascist dictatorship. Like the Ayotzinapa 43, quite a number of them were teachers.

For its colonialism, and later support of dictators, Spain has a lot to answer for, and doesn’t want to face up to this, I said.

“No, no,” she said. “That’s the Black Legend.” The “black legend” of Spain originated among Protestant propagandists in the 17th century to defame the Catholic colonists.

Image by Protestant artist DeBrys illustrating the "Black Legend"

Don’t fret, I replied. The English have plenty to answer for in their own colonial times, since their Royal African Company, chartered and owned by the crown, imported more slaves to the Americas than any other enterprise.

Logo of the English Royal African Company

I pass through that grim gallery to one hung with t-shirts. There’s a video of a woman putting on one after another of them – it’s a bit of comic relief. “Graphic bodies”, it’s called, “matrices for a street choreography”. I love radical movement t-shirts and collect them for Interference Archive in Brooklyn.

They’re important in Spain. They cohere and mark out masses of demonstrators. And in other contexts t-shirts make individual statements amongst the throngs of ‘normals’ dressed as corporate billboards. During the 15M encampment in May of 2011, there was a guy who photographed everyone’s he could find.

“Giro” shows also the street stencils of artists like the Chilean Luz Donoso. Often these are just faces, or pared-down abstract images which furtively convey a message everyone understands. (Similar brief crypto-significations are happening today in Russia and Iran.)

Uruguayan photographer Juan Angel Urruzola’s wide murals recall those who should be seniors now walking the streets of their cities, but instead are merely ghosts.

An installation titled “Malvenido Rockefeller” (not “welcome”, bienvenido, but its opposite) documents posters and paintings from 1969. They were put up on the streets to greet the VP’s tour of South America. During that same year, the Art Workers Coalition in NYC was protesting Nelson’s family control of the MoMA, a tiny issue compared to the partnership of the US government and Standard Oil in exploiting Latin American countries.

Change has happened over the intervening 50 years. Still, today, can you imagine this exhibition at any NYC museum?

Large parts of “Giro” are given over to LGBTQ groups and movements, like the humorous Lesbianos Fugitivos map of the “coño Iberoamericano”. And, like the massive “Perder la Forma” show (2012) before it, “Giro” features archival zines which show the long struggle of LGBTQ peopls in America Sur.

“Cuir Library” is a pink-walled reading room with two giant tit-like cushions to recline on, and dozens upon dozens of fanzines to browse. (“Cuir” is where the zine energy is these days, as the recent Pichi Fest at the ESLA Eko in Madrid showed.)

An installation of vintage queer publications complemented the library.

On one wall is Chilean artist César Valencia’s painting, Producción Gráfica Medicina Emocional (2018-22), an attempt to come to grips with all of this history. It’s like a mechanical metaphor for the “Giro” show itself. Valencia’s diagrammatic reflection on the pasts of Chile and Argentina is part of the show’s “In Secret” ensemble.

Reason breaks down in the room of relics of the Ayotzinapa massacre of 43 teachers in training in Guerrero, Mexico in 2014. The agitation behind these killings has rocked the country since then with the slogan, “Alive they took them, alive we want them”.

43 needlework remembrances of each of these young men, stitched with iamges of turtles, corn, and childhood things are hung across the space in a room the curators call “The Delay”.

Parading embroideries in Mexico

These are “actions performed in slow time over a long duration”. Besides the Ayotzinapa 43, embroideries from Brazil recall Marielle Franco, the assassinated trans legislator.

Stitchings by the Fuentes Rojas collective (2011-19) recall the murdered of Mexico, most of them femicides. “Una victima, una panuela”; there were curtains of these kerchiefs that were also carried in the streets.

Imagining a whole string of these murders is the hard work Chilean novelist Roberto Bolaño undertook in his great book 2666.

These embroideries by collectives of women are “an interpellation that passes more through the senses than the reason, by marking the loving manual work that builds a visuality that informs, denounces and shares. Love as a political concept in action” (“Gira” catalogue, p. 107).

My artist friend said that when he saw them he cried.

Things get a little more proactive in the part of the show called “Territorios insumisos”, insubordinate territories. Here is a (comparatively) tiny version of the giant pedagogic map the Beehive Collective used to draw “parallels between colonial history and modern-day capitalism”.

“Capitalism,” the poster declares: “Every time history repeats itself, the price goes up.”

We move into America Norte through a room of material about Nicaragua which repeats the epochal political art installation form of Group Material in 1984, their “Timeline: The Chronicle of US Intervention in Central and Latin America” installed at P.S. 1. The installation, by [Experimental Graphics Collective?], concludes with a sad image of opposition politicians being arrested by the government of the corrupted Sandinista Daniel Ortega.

In the gallery dedicated mostly to work from America Norte we find Standing Rock posters by U.S. graphic artists familiar from the work of JustSeeds and the Interference Archive in Brooklyn – #NoDAPL!.

Most spectacular is the tipped-up long house relatinig to the Zapantera Negra project. This construction, with painted murals outside and hung inside with tapestries made by Zapatista women, was installed for the show by California artist Caleb Duarte. He’s part of the team of artists in solidarity with the Zapatista movement working out of an occupied building called EDELO (En Donde Era la ONU / Where the United Nations Used to Be).

Between 2012-16, the Zapantera Negra project brought together the artist Emory Douglas, former Minister of Culture of the Black Panther Party, and collectives of Zapatista women resulting in remarkable syncretic works linking the two movements.

Both the Zapatistas of Chiapas and the Black Panthers before them were/are armed liberation movements which had to deal in the face of overwhelming state power arrayed against them. Yet they persist – in Chiapas as a de facto autonomous zone, and in the “KKK USA” in the form of a powerful and influential historical example, and direct inspiration for present-day projects of black autonomy like Cooperation Jackson.

The Zapatistas continue to be a blacklight beacon of possibility. They inspire many, as evidenced in the the 2021 anthology When the Roots Start Moving produced by Alessandra Pomarico and Nikolay Oleynikov of Free Home University and Chto Delat respectively. (Their project was the subject of a post last year on my increasingly related blog “Occupations & Properties”.)

Emory Douglas in Chiapas

For them the Zapatistas represent “a home (or a homecoming) for our hopes and political imaginaries, providing a praxis to learn from and with.”

This is a long way from hippies wearing beads and taking peyote, i.e., an essentialist romantic identification with indigenous peoples and struggles. This is the evolved position of left cultural actors and thinkers in solidarity with anti-capitalist anti-colonial native-led movements. #IdleNoMore en soli con #ExtinctionRebellion

All in all, “Giro” is a deeply thought profoundly complex political art exhibition. The subtitle comes from a song lyric, the chorus, by Violeta Parra, “Volver a los 17”, just as the earlier related show “Perder la Forma” title came from a poem –

Se va enredando, enredando

Como en el muro la hiedra

Y va brotando, brotando

Como el musguito en la piedra

Ay sí sí sí

(It gets entangled, entangled

Like the ivy on the wall

And goes sprouting, sprouting

Like the moss on the stone

oh yeah yeah yeah)

“Here,” as written on the wall text, “the graphic turn is understood as a recurrent political matrix.” The “hut” of the Zapantera Negra project, posters from the Chicano movement of 1969-72, graphics from Pasofronteras/border crossings activisms, classics from the OSPAAAL anti-imperialist project est. in Cuba in 1966, #BLM “my life matters” martyr-portrait images – all of this activism is transversal, and increasingly networked.

As always with the Reina Sofia exhibitions it’s too much – but seriously, it’s never enough for not just memorializing but inspiring ongoing activism and agitation.

The “Agora of the Present” tries to be that, a zone of rabble rousing. Three screens fire up sequentially, the most unignorable black-clad troupes of women shouting in unison at the “rapist in your path” (Sandi Bachom, 2020) – a spectacle of unity and accusation.

We sprout on.

Next stop for the show:

Museo Universitario Arte Contemporáneo de la Universidad Autónoma de México (MUAC), Ciudad de México (noviembre, 2022 - julio, 2023)

LINKS& REFERENCES mentioned in the text

Pinochet's troops round up people on the streets in Chile, September 11, 1973

Graphic Turn: Like the Ivy on the Wall

https://www.museoreinasofia.es/en/exhibitions/graphic-turn

exhibition handout in English

https://www.museoreinasofia.es/sites/default/files/exposiciones/exhibition_information_sheet_graphic_turn.pdf

See this pedagogical guide “HOW to '92” produced by the Alliance for Cultural Democracy and posted in full at Gregory

Sholette’s “Dark Matter Archives”

http://www.darkmatterarchives.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/HOW-TO-92-small-file.pdf

Bartolomé de las Casas.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bartolom%C3%A9_de_las_Casas

Environmental Defender Killed Every Two Days Over Last ...

https://www.commondreams.org › ...

29 sept 2022 — The report—entitled Decade of Defiance: Ten Years of Reporting Land and Environmental Activism Worldwide—underscores how land inequality and ...

One minute video presents the report

https://twitter.com/Global_Witness/status/1575366478483841025

Carolina Caycedo, “La Siembra – The Sowing”, e-flux online, #129, September 2022

https://www.e-flux.com/journal/129/484604/la-siembra-the-sowing/

Red Conceptualismos del Sur

Plataforma de investigación, discusión y toma de posición colectiva desde América Latina. Fundada en 2007

https://redcsur.net/

The “Mapoteca” of the Iconoclasistas collective

https://iconoclasistas.net/cartografias/

Black Legend (Spain)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Black_Legend_(Spain)

Royal African Company

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Royal_African_Company

Cristina Híjar González, "Giro gráfico. Como en el muro la hiedra", Posted on 6 junio, 2022

"Breve e incompleta crónica de la exposición internacional de acciones gráficas y visualidades de la RedCSur en el Museo Reina Sofía" on a Mexican blog

https://piso9.net/giro-grafico-como-en-el-muro-la-hiedra/

Fotos de camisetas en ANIVERSARIOS del 15-M: – Kaos en la red

https://archivo.kaosenlared.net/fotos-de-camisetas-en-aniversarios-del-15-m/

Pichi Fest (@pichifest) • Instagram photos and videos

https://www.instagram.com › pichifest

Festival de fanzines transfeminista y autogestionado en Madrid

Iguala mass kidnapping (2014) – the Ayotzinapa inicident

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Iguala_mass_kidnapping

Fuentes Rojas. Bordando por la paz y la memoria. Una víctima, un pañuelo

includes 13 minute video interview

https://www.museoreinasofia.es/coleccion/restauracion/fuentes-rojas

citation from "La Demora" (the delay), by Cristina Hijar, Elva Peniche and Sylvia Suarez in the catalogue of the show, p. 107. O.P. Assisted machine translation.

“Mesoamérica Resiste”, from the Beehive Design Collective

https://beehivecollective.org/posterViewer/?poster=mr

Timeline: The Chronicle of US Intervention in Central and Latin America. 22 January – 18 March, 1984. on Doug Ashford's website

http://www.dougashford.info/?p=581

Zapantera Negra (Updated and Expanded Edition)

https://www.commonnotions.org/zapantera-negra-updated

Caleb Duarte’s website with material on the Zapantera Negra project

https://www.calebduarte.org/zapantera-negra

Blog post on t“When the Roots Start Moving” book with editor interview, October 19, 2021 “On Learning and Un-learning”

http://occuprop.blogspot.com/2021/10/on-learning-and-un-learning.html

see also a Canadian appearance by those two at:

https://musagetes.ca/news/when-the-roots-start-moving/

Next stop for the “Gira” show:

Museo Universitario Arte Contemporáneo de la Universidad Autónoma de México (MUAC), Ciudad de México (noviembre, 2022 - julio, 2023)

https://muac.unam.mx/

Warriors waiting at Wounded Knee, 1973

Saturday, October 1, 2022

A Visit to the Watchtower

The assembly at La Atalaya

The pandemic seems to have let up, or at least the sky is clearing. I got the ‘Rona at last. It wasn’t fun, but it wasn’t severe. Definitely a new disease. But in Madrid, folks are walking around and interacting without masks, although on public transit most people still wear them.

Recently I was invited to a fiesta at CSO La Atalaya in Valekas. It’s something of a trip out there. I missed the play of the "marionetas subversivas", but I had some paella at the “comida popular”.

Heading to the fiesta

The okupa La Atalaya is an abandoned school, and the fiesta took place in the expansive playground. I can't say when it was first occupied, but the blog starts in 2015.

Vallecas is a peripheral barrio of Madrid. It began as a "chabola" or "favela" in agricultural land decades ago as laborers came from the Spanish countryside to work in Madrid's factories. They were organized by the Communist Party to demand proper housing, and the struggle was a hard one. Finally public housing was built. The barrio remains solidly working class.

Undated photo, 1960s? Vallecas was called "little Russia" in the last century

Atalaya means "watchtower". In their occupation statement, they said: “We want to be the engine of cultural recovery and sovereignty for Vallekas, returning to being what we should never have ceased to be... As we said the first day we started, paraphrasing Pablo Neruda: “It is forbidden not to smile at problems, not to fight for what you want, to abandon everything out of fear, not to make your dreams come true”.

"Alegría para combatir, organización para vencer". "Joy to fight, organization to win."

The center is where the "pirate ship" of the annual July Naval Battle of Vallecas is ‘launched’ – built and rolled out to the streets. This construction plies the local ‘waters’, the crowds that gather to drench each other with water in the annual July event in the streets of the barrio.

A mural recalls the 'pirate ship' of the annual 'naval battle' (giant water-gun fight) in the barrio

In May, when an order of eviction came down, La Atalaya called a press conference. Publico reported that by then the old school had a climbing wall, a skate park, sports teams, and a “pole dance” project. I think this is more likely an aerial silk project, since they performed in that way at the fiesta. A long hanging fabric is used as a performance armature for twisting and climbing movements.

Atalaya was founded as a youth center. Publico quotes a young man, Daniel, "We have allowed young people to have free activities in an area with few resources”. During the pandemic, some residents of the neighborhood ran a solidarity food pantry, Somos Tribu, which served 200-300 people weekly.

"These spaces help create community,” He said. “We are isolated in our homes and we believe that we have no help or alternatives, but the social centers help us understand that problems are collective, and that we have to find solutions together."

Climbing wall in La Atalaya

After a judicial order to vacate, delivered in May of this year, La Marea made a video which reveals what an extraordinary project this CSO is.

In this “day-to-day” video, produced for El Salto magazine, you can see the climbing wall, a boxing club, a skate park, with hands-on guided instruction, and a solidarity food pantry. The place even has a library with language classes and events. The narrator speaks of youth at risk in an educational system that isn’t adapted to their realities.

The food pantry is for people with “renta minima”, an income of 700 Euros a month. An organizer notes that there are many ideologies in the neighborhood, Christians, Muslims, atheists, and those “who wave the flag” (nationalists). This is a “human project”, he says, during a time when many social services are closed.

La Atalaya was not evicted in May. They recently won another court victory, as activists up on criminal charges were acquitted. Still, like all the okupas of Madrid, regardless of the important services they provide to citizens, the fate of La Atalaya is highly precarious.

#CSOAtalaya

LINKS

CSOA La Atalaya represents itself, with bulletins and a rad short video

https://www.facebook.com/CSOJAtalaya

about CSOA La Atalaya

https://vallecasviva.com/espacio-kult/cso-atalaya-vallecana/

Irene Gonzalez Rodriguez, “Madrid acorrala aún más a los espacios sociales: el centro La Atalaya se enfrenta a un nuevo desalojo”, Publico, 05/12/2022

https://www.publico.es/sociedad/madrid-acorrala-espacios-sociales-centro-atalaya-enfrenta-nuevo-desalojo.html

A May, '22 tour video by Oriol Daviu of La Marea, narrated by young woman organizers

"El día a día del CSO Atalaya, de Vallecas, obligado a desalojar el centro"

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nVCy8Z6Zkhw

Eli Lorenzi (@elisabeth.lorenzi)

In the plaza at La Atalaya. Lucio Urtubia was a famous Spanish anarchist

Saturday, September 24, 2022

La Quimera Flickers Out

[NOTE: If you just want the news of the eviction, and a short primer on the history of La Quimera – go to “Madrid No Frills” new post. What follows is a rumination on the eviction and the past of the place, a ‘long read’.] References are below the text.

So Wednesday morning the occupied building called La Quimera in the Lavapies barrio of Madrid was evicted. It had been tagged as a “narcopiso” – a drug-dealing and -taking occupied flat – by the rightwing press. For sure the giant apartment building on Nelson Mandela plaza had plenty of problems.

“Narcopiso” in U.S. English is a “shooting gallery”. It is a slur on a complex social situation in a building with a deep history in the Madrid okupa movement.

What was really going on in this building? 70 people were living there, mostly African migrants. There was a bar on the ground floor, likely non-alcoholic since the clients were mostly Muslim.

Leah Pattem, the English language Madrid journalist who runs “Madrid No Frills” (her reporting is referenced above) tweeted “This morning, around 70 unofficial residents of #LaQuimera in Lavapiés were evicted without any solution. Police walked a dozen men down calle Mesón de Paredes, out of sight of the press, then left them to disappear into the streets.” @LeahPattem

El Pais reported that neighbors had asked the owner to demand the removal of the squatters so that the police could act to clear out the building. Everybody is happy that it’s closed, they say.

The rightwing mayor, elected with a minority of votes by a process I still don’t understand (get ready USA) crowed how happy he was that this “agujero negro” (black hole) had been cleaned up.

Destroying Citizen Participation in Madrid

The rightist coalition beat Manuela Carmena in the elections for mayor. Manuela’s party, Mas Madrid, was expected to win, but the left split and the right came to power in both the city and the province. Part of the split was because Manuela didn’t support the social centers. At least she didn’t launch an eviction campaign. She was the least worst option to vote, but too few people think that way.

Mayor Almeja has evicted many legalized contracted citizen-run spaces, and several okupa social centers in his policy of “zero tolerance” for ‘squatters’. That intolerance extends to any place where citizens might organize outside of normative state channels. The campaign is accompanied by the usual scare-lies in the press about junkies taking over your country house.

Directly after their electoral triumph in the city of Madrid, the right went on a revanchist rampage of closures. It began with La Gasolinera (@LaGasoli) in 2019.

La Gasolinera was an innocuous place, full of parents and kids. But they showed a film that the neighborhood councilman didn’t like, and that Vox man, the neo-fascist political party with whom the Partido Popular “center right” has allied, demanded the place be closed. Thereafter they didn’t give any excuses. They just evicted places and cancelled contracts. I’ve lost count, but it must be close to a dozen citizen-run spaces closed. Madrid is becoming a desert for open-door places.

This campaign, which is hardly finished, gets petty: Most recently in the Lavapies neighborhood agents of the city tore up a tiny patch of land – Replantamos Plaza Lavapiés – that had been planted with flowers and vegetables. The activists replanted it.

Impromptu Homeless Shelter

In her report of that day, @LeahPattem tweeted that La Quimera had become “an informal shelter for homeless people, many of whom are undocumented migrants, and some have mental health issues and PTSD from their journey to Spain. Today, these people are back on the streets and La Quimera is empty.”

There’s no question that the place was troublesome for the neighbors. The grand plaza that La Quimera faces, named for an African hero, is ringed by stores, cafes and other apartment buildings. When there’s screaming, fighting, fires and ruckus, everyone gets upset.

So What Happened? We Don’t Yet Know

For years, even decades, La Quimera was a useful social center. In the late ‘90s, the partly-constructed abandoned building was occupied as part of the famous series of Laboratorio okupas. A Vallecana activist told me she had lived there then. But it wasn’t congenial – no water, no power. A hard place to be.

Happier days for La Q. The bar in 2016, @largarder81

According to the movement wiki 15Mpedia (at: https://15mpedia.org/wiki/CSROA_La_Quimera), the CSROA La Quimera is – was – a re - squatted social center. ("CSROA" they call it. CSOA is Centro Social Okupado Autogestionado; "R" for "recuperado").

La Quimera was re-squatted in the spring of 2013 during the “Toque a Bankia” campaign, a coordinated hacking and squatting wave that responded to the corruption of a major Spanish bank, corruption that finally sent the ex-finance minister, Rodrigo Rato, to jail.

La Quimera Feminista

When I came upon it, La Quimera was run by a radical feminist collective. They had a bar, held events, made posters and t-shirts – normal punky okupa stuff. They’d given keys to a group of African migrants who were attempting to organize a union of street-sellers, the Sindicato de los Manteros. An arts agency, Hablar en Arte, funded a public art project wherein two artists, Byron Maher and Alexander Ríos Pachón, worked together to support the formation of this nascent group. I was asked to write about it.

Byron and Alex made banners, took photos, and organized an event at La Ingobernable, a social center next to Medialab Prado. (La Ingob had water and power, so people could cook.) A former health center squatted in 2017, the place, like La Quimera, was also a strongly feminist okupa project, was. It was evicted in 2019, directly after the election of the rightwing Mayor Almeida.

When La Ingobernable Was Still in Play

La Ingob's doorway can be seen in the distance; in foreground, the "green wall" of the Caixa Forum exhibition space.

La Ingobernable was also a player in this story. Like the Laboratorio before it, Ingobernable was a long-term project with several occupations and evictions. Writes Leah Pattem: “La Ingobernable began in 2000 with the aim to fill the support gap caused by Madrid’s shrinking public services. This independent collective provide[d] information, advice and support in housing, mental health, gender violence, immigration and more, depending on the skills of the volunteers involved.”

As a key center of organizing for things like the massive 8M feminist march, the rightwing city government needed to evict them. That was also vengeance. Followers of this blog will have read of La Ingobernable’s key role in partnership with the official city project Medialab Prado, as a nerve center of social movement alliance with the short-lived municipalist government.

(The municipalist platform of Manuela Carmena, however, did not give La Ingob a contract of tenancy when they could have. Not that a contract would have protected them from the revanchists; it would have delayed them.)

A Union for Migrant Street Vendors

I attended numerous meetings at La Quimera of the prospective sindicato of manteros, which was also supported by activists from SOS Racismo. Occasionally the artists would attend. (I was the old white guy taking notes in the corner, who didn’t understand much of what was going on.) The collaboration of the artists with the manteros unfolded during the brief warm progressive thaw of governance in Madrid as institutions and foundations began to stretch out their tender tentacles towards social movements.

Finally I submitted a long text on the process of Byron and Alex’s complex project with the manteros. The text was first edited, then cut from the book published by the Collaborative Arts Partnership Programme (CAPP) “an ambitious transnational cultural programme focusing on the dynamic area of collaborative arts” at: https://www.cappnetwork.com/.

Meeting of manteros' assembly at La Quimera, ca. 2018

Major meeting of manteros and Afropean speakers from Madrid and other cities at Medialab Prado, ca. 2018

It always stings when a text is rejected. I intended to post the text, but life intervened, and other projects. (I have a new book! https://alanwmoore.net/memoir/ ) It’s four years later, and a new epoch after the major threats of Covid virus have lifted. So I’ll soon try to post the finished unpublished text to my page at academia.edu – https://independent.academia.edu/AlanWMoore.

A Store for the Union

I didn’t follow this story after the fracaso with HablarenArte. The Sindicato de Manteros seems to have done okay. They are constituted, with a website, and there is now a store, opened last year, called “Pantera”. They sell the clothing brand Top Manta, produced by the Barcelona street vendor initiative.

After the social and economic trauma of the virus and its lockdowns, everything has become more unstable. Government repression and violence, however, has continued unimpeded. A delicate project like La Quimera – volunteer, ideologically motivated, rough material conditions – became corrupted. Crime never sleeps, and it doesn’t wear a face mask.

A Loss for the Autonomous Movements

I don’t know what happened, and I don’t know who does. I can only say this is a failure of autonomous management. No one in governance has an interest in the success of autonomy. It's not a hard thing for police undercover operations to destabilize volunteer projects. Both Swiss and NYC activists have noted how cops directed narcos and dealers to their occupied places, told them they wouldn’t be arrested if they worked there. Did the same happen at La Q? Without a diligent assembly, it easily could have, since the virus broke the organization in many places. And "easy" is what cops like to do.

In a Utopic City, it Coulda Been Different

Solutions can be found to the problems that beset La Quimera. "Narcopisos" can be eliminated by providing addicts with safe injection spaces. In effect, “narcopisos” are privatized safe injection spaces run by criminals, complete with illicit pharmacies. Drugs can be legalized, regulated and taxed. Desperate migrants eager to work can be absorbed into the workforce by giving them papers so employers can hire them. (They do so anyway in the agricultural districts, for slave wages, papers or no.)

But solutions aren’t what politicians seek. Here they still cut off the power for months to the peripheral barrio of racialized people called Canada Real on the pretext that the district is full of marijuana plantations. ‘Look at the fancy cars parked there,’ say the supposed leaders of Madrid. (The UN charged that the situation was a violation of childrens’ rights; but you know, George Soros?)

Punks + Crooks + Useful Fears